Article of the Week: TIND implantation in benign prostatic obstruction

Every Week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

Finally, the third post under the Article of the Week heading on the homepage will consist of additional material or media. This week we feature a podcast discussing the paper.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

3‐Year follow‐up of temporary implantable nitinol device implantation for the treatment of benign prostatic obstruction

Abstract

Objectives

To report 3‐year follow‐up results of the first implantations with a temporary implantable nitinol device (TIND®; Medi‐Tate Ltd., Or Akiva, Israel) for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Patients and Methods

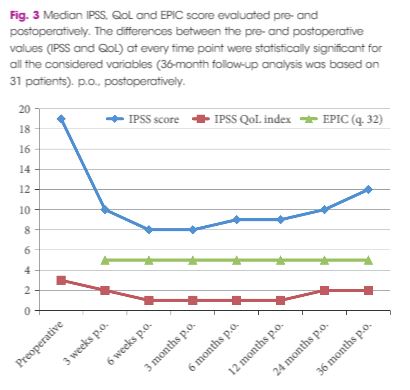

In all, 32 patients with LUTS were enrolled in this prospective study. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee. Inclusion criteria were: age >50 years, International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) ≥10, peak urinary flow (Qmax) <12 mL/s, and prostate volume <60 mL. The TIND was implanted within the bladder neck and the prostatic urethra under light sedation, and removed 5 days later in an outpatient setting. Demographics, perioperative results, complications (according to Clavien–Dindo classification), functional results, and quality of life (QoL) were evaluated. Follow‐up assessments were made at 3 and 6 weeks, and 3, 6, 12, 24 and 36 months after the implantation. The Student’s t‐test, one‐way analysis of variance and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for statistical analyses.

Results

At baseline, the mean (standard deviation, sd) patient age was 69.4 (8.2) years, prostate volume was 29.5 (7.4) mL, and Qmax was 7.6 (2.2) mL/s. The median (interquartile range, IQR) IPSS was 19 (14–23) and the QoL score was 3 (3–4). All the implantations were successful, with a mean total operative time of 5.8 min. No intraoperative complications were recorded. The change from baseline in IPSS, QoL score and Qmax was significant at every follow‐up time point. After 36 months of follow‐up, a 41% rise in Qmax was achieved (mean 10.1 mL/s), the median (IQR) IPSS was 12 (6–24) and the IPSS QoL was 2 (1–4). Four early complications (12.5%) were recorded, including one case of urinary retention (3.1%), one case of transient incontinence due to device displacement (3.1%), and two cases of infection (6.2%). No further complications were recorded during the 36‐month follow‐up.

Conclusions

The extended follow‐up period corroborated our previous findings and suggests that TIND implantation is safe, effective and well‐tolerated, for at least 36 months after treatment.