The optimisation of radical external-beam radiotherapy treatment is ultimately a compromise. The aim is to deliver a clinically effective radiation dose to the tumour target, whilst limiting the irradiation of surrounding normal tissue to minimise acute and late side effects. Modern image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IG-IMRT) allows very accurate treatment delivery, which improves this therapeutic ratio. However, there are limitations in its ability to reduce toxicity, due to the constraints of regional anatomy and the physical properties of photon beams. A variety of additional organ-specific techniques exist to further minimise the impact of radiotherapy on adjacent healthy tissue. These range in complexity from ovarian auto-transplantation in selected patients awaiting pelvic radiotherapy for gynaecological malignancies, to delivering radiotherapy for left-sided breast cancers at inspiratory breath-hold to maximise the distance of the chest wall from the left anterior descending coronary artery.

For prostate cancer radiotherapy, the normal structures that determine the optimal safely deliverable dose include the rectum (anterior rectal wall), bladder, femoral heads and penile bulb. IG-IMRT has facilitated dose-escalation, and the treatment of patients previously considered to be ineligible for a radical treatment; both with acceptable toxicity. Higher doses result in improved prostate-cancer biochemical (PSA) control rates, and metastasisfree survival, but as yet no overall survival benefit has been demonstrated in individual trials, despite 10-year follow-up [1]. This may due to the long natural history of localised prostate cancer, the impact of competing comorbidities [2], and the ever-increasing efficacy of treatments for metastatic disease on relapse.

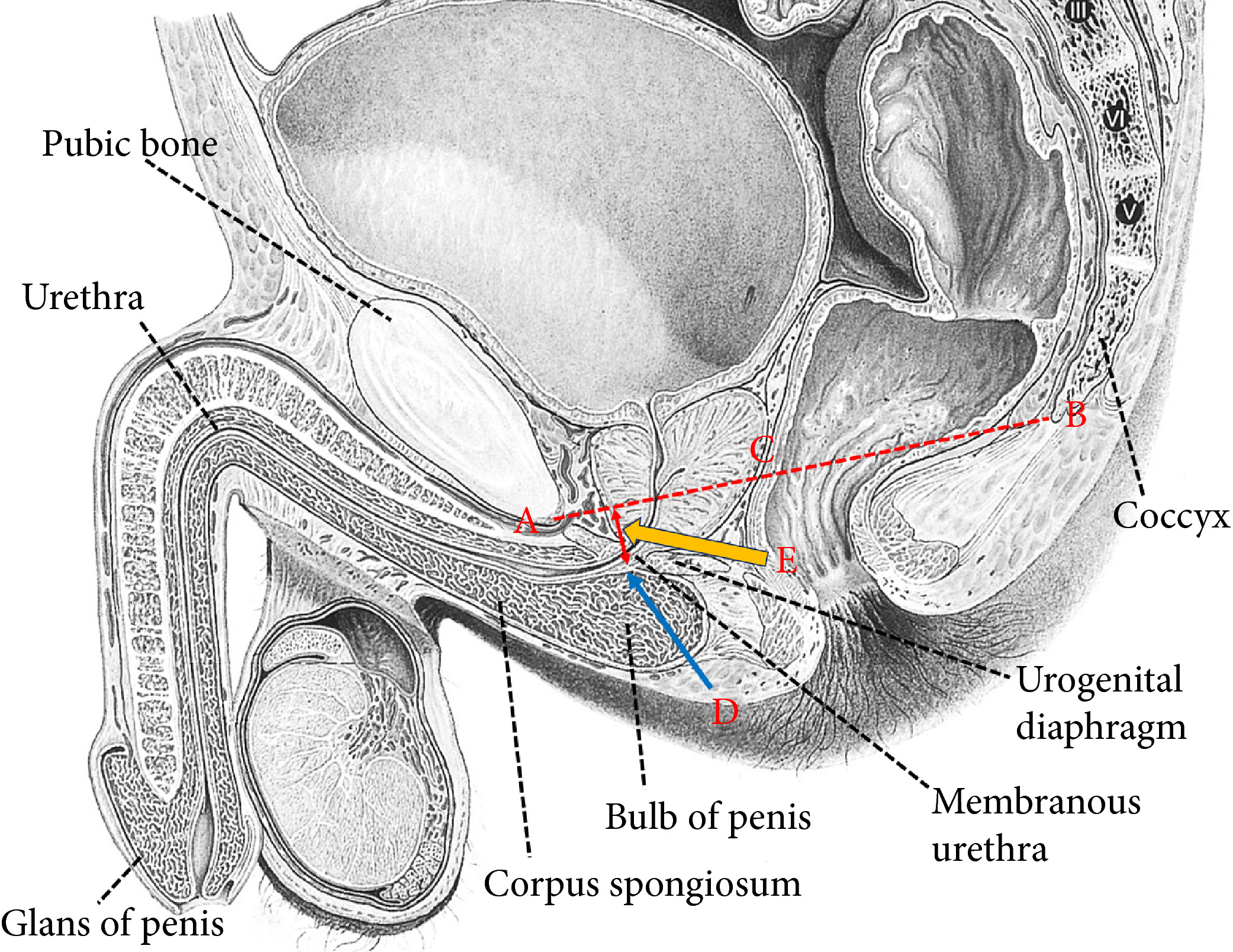

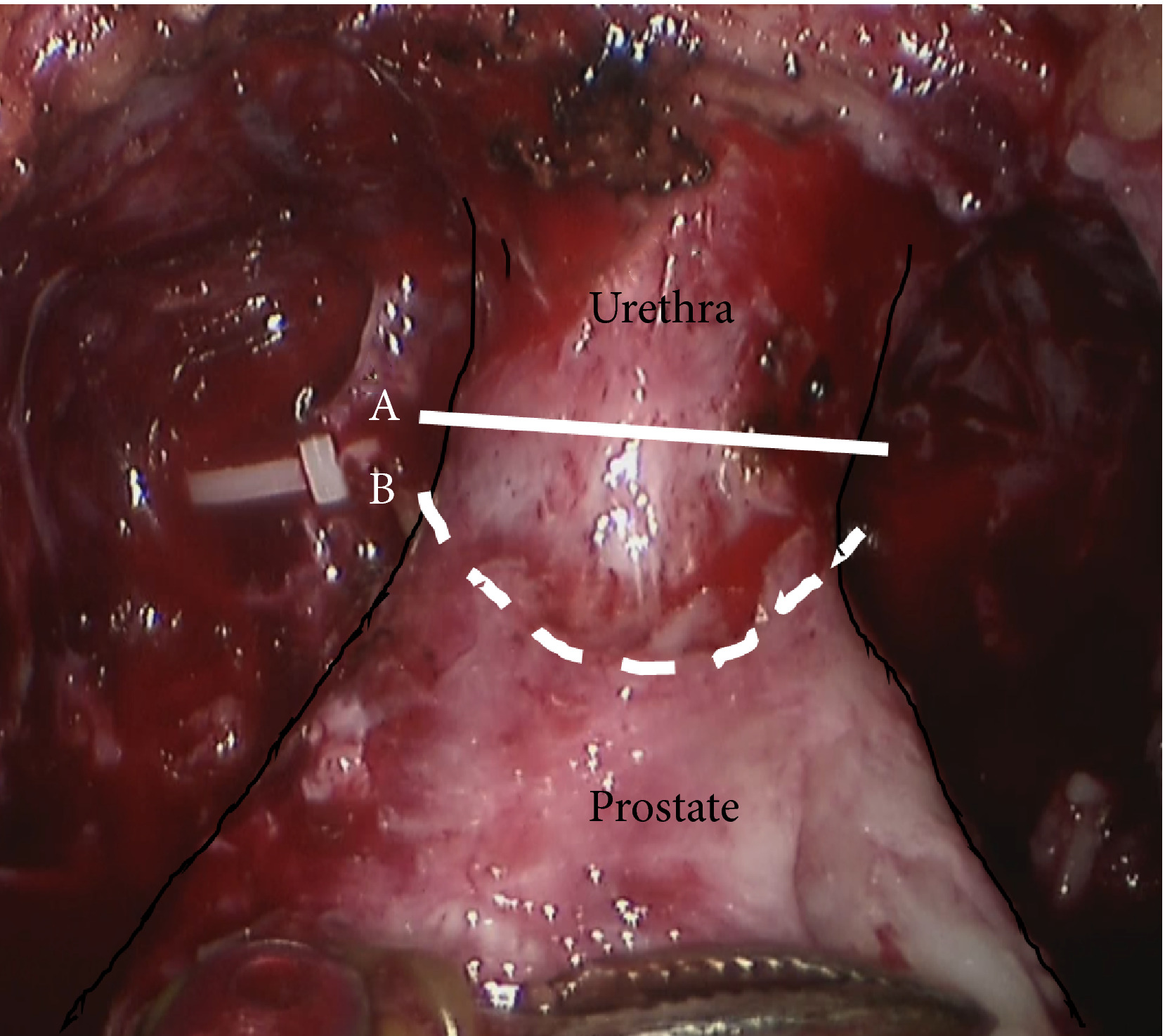

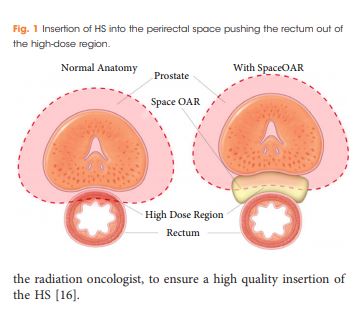

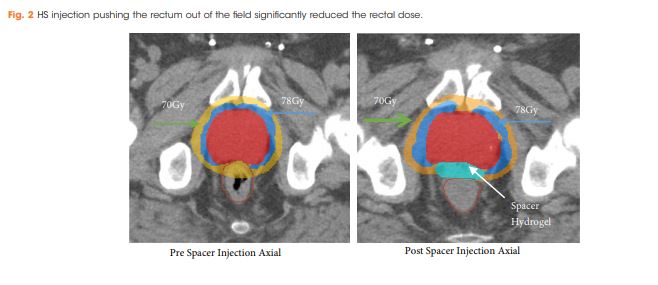

Rectal spacers are a further refinement to the delivery of radical IG-IMRT to the prostate gland. By inserting a biodegradable substance / inflatable biodegradable balloon into the anterior perirectal space, the distance between the prostate and the anterior rectal wall can be increased by approximately 1cm. This reduces the volume of rectum lying within the high-dose radiation field, thereby reducing late bowel toxicity. A recently reported randomised Phase III trial found a reduction the 3-year incidence of ≥ Grade 1 and ≥ Grade 2 rectal toxicity (9.2% v 2.0%; p=0.28; and 5.7% v 0%; p=0.12 respectively) with the addition of a rectal spacer [3]. This was in a very select group of patients: PSA ≤20, cT1-2, International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Prostate Cancer Grade 1-3 (<50% of cores involved), prostate volume <80cc, no use of androgen deprivation therapy, and the use of MRI-CT fusion to aid prostate delineation during the planning process.

In this issue of the BJUI, Chao et al. [4] report their prospective single-centre experience of using a rectal spacer device. This is not a randomised study, and no control arm exists to assist in quantifying the clinical impact of inserting a spacer. However, the patient population studied closely reflects that undergoing radical radiotherapy in most oncology departments world-wide. There were no limitations placed on prostate size (45% were 50- 100cc; 17% >100cc; maximum 187cc), PSA (10% had a PSA >20; maximum 117), or ISUP histological grade (27% were Grade 4 and 5); and 27% of patients were cT3a on imaging. They demonstrated that spacer insertion was safe across a diverse population of men with localised prostate cancer. Further, acceptable prostate-rectal wall separation and rectal dosimetry could be achieved irrespective of prostate size – which was reflected by the low rates of cumulative late rectal toxicity when assessed at a median follow-up of 14 months.

As with any new technique, additional clarification is required to determine exactly where rectal spacers fit into the radiotherapy armoury. In the study by Chao et. al. the Radiation Oncologists did not have access to CT-MRI fusion at the planning stage. As the electron densities for the prostate, rectal-spacer and rectal wall are similar, it can be challenging to determine the anatomical boundaries on CT alone. However, if growing clinical experience now permits accurate delineation by merely adjusting the window levels on the Planning CT, this could facilitate more widespread introduction of the technique, outside the specialist centres with MR-fusion capabilities.

Patient selection is also key to the introduction of this technique. Patient series have reported the safety of the spacer insertion technique across a range of prostate sizes, and prostate cancer risk groups. However, prospective randomised data is lacking on whether treatment efficacy is affected by using a spacer in high-risk / locally advanced disease – the population most likely to benefit from dose-escalated radical radiotherapy [5]. Further, in the only randomised study to date, >90% of patients in the control arm experienced no late rectal toxicity, and >94% experienced no ≥Grade 2 rectal toxicity. Based on long-term follow-up data from the RT01 study, this was an appropriate time-point at which to assess late bowel toxicity, which peaks at 12-36 months before declining [6]. Therefore, the majority of patients do not experience clinically significant late toxicity even without a spacer.

Rectal spacers have the potential to make a valuable contribution to radical IG-IMRT treatment for localised prostate cancer. However, predictive factors are required to identify which patients are likely to benefit from the technique. For many patients, with access to the latest radiotherapy planning and delivery systems, spacers may represent an additional costly procedure with limited benefit.

S.R.Hughes

Oncology Department, Guy’s & St. Thomas’ NHS Trust, London, UK

References

1. Dearnaley DP, Jovic G, Syndikus I, et. al. The Lancet Oncol. 2014; 15(4): 464-473

2. Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, Lin Y, DiPaola RS, Yao SL. Fifteen-year outcomes following conservative management among men aged 65 years or older with localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015; 68(5): 805-11

3. Hamstra DA, Mariados N, Sylvester J et. al. Continued Benefit to Rectal Separation for Prostate Radiation Therapy: Final Results of a Phase III Trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017; 97(5): 976-985

4. Chao M, Ho H, Chan Y et. al. Prospective Analysis of Hydrogel Spacer for Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiotherapy. BJUI 2018

5. Kalbasi A, Li J, Berman AT. Dose-Escalated Irradiation and Overall Survival in Men with Non-metastatic Prostate Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015; 1(7): 897-906

6. Syndikus I, Morgan RC, Sydes MR, Graham JD, Dearnaley DP. Late Gastrointestinal Toxicity After Dose-Escalated Conformal Radiotherapy For Early Prostate Cancer: