Article of the week: RP and the effect of close surgical margins: results from the SEARCH database

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Radical prostatectomy and the effect of close surgical margins: results from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) database

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate biochemical recurrence (BCR) patterns amongst men undergoing radical prostatectomy (RP) with specimens having negative (NSM), positive (PSM), and close surgical margins (CSM) from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) cohort, as PSM after RP are a significant predictor of biochemical failure and possible disease progression, with CSM representing a diagnostic challenge for surgeons.

Patients and Methods

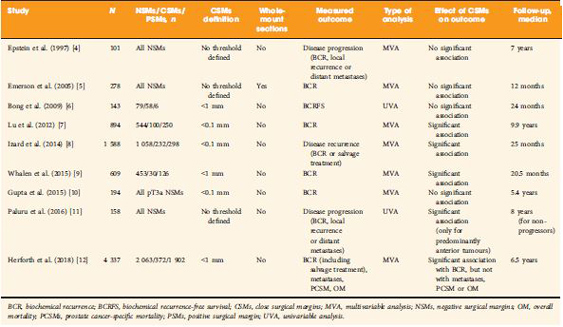

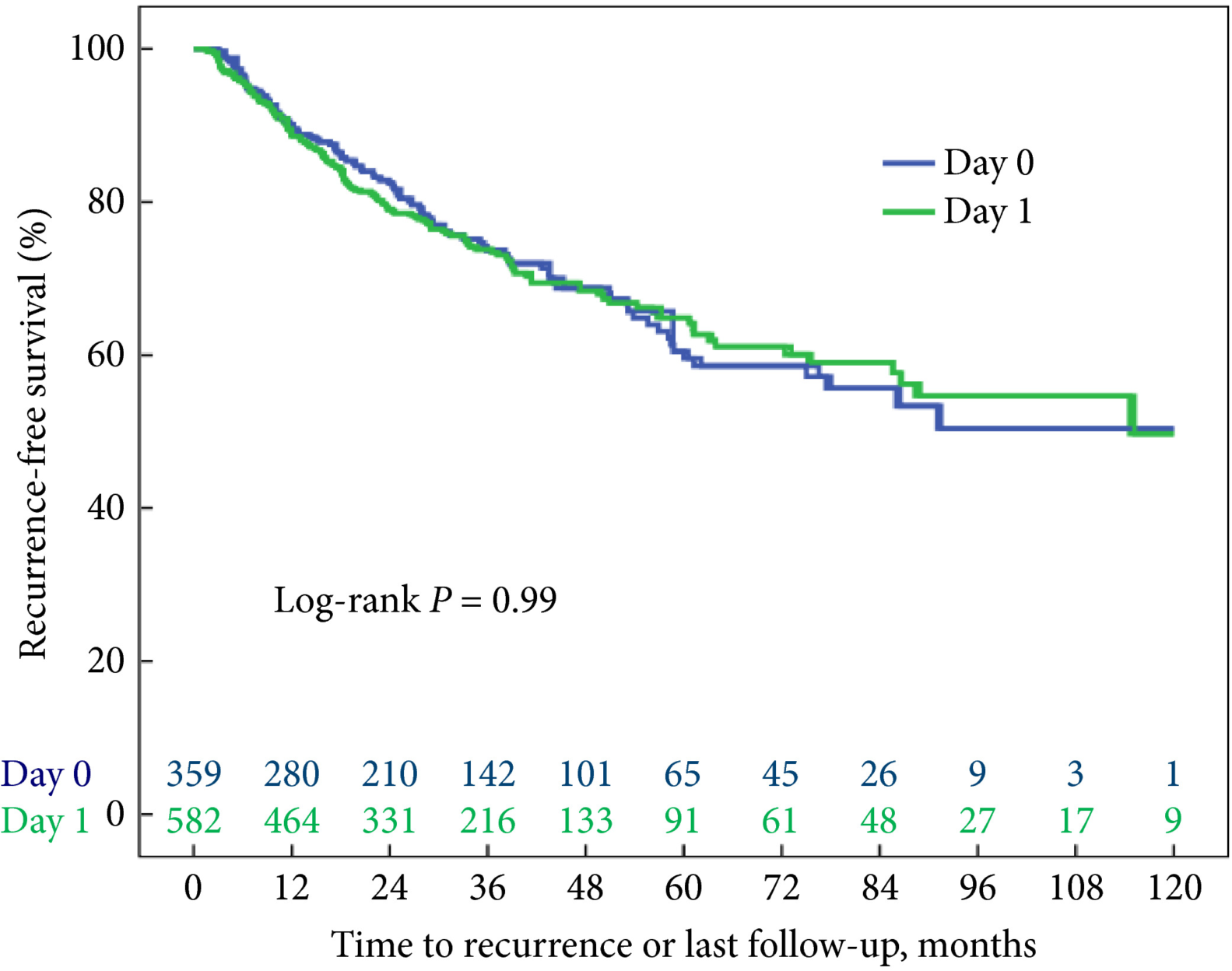

Men undergoing RP between 1988 and 2015 with known final pathological margin status were evaluated. The cohort was divided into three groups based on margin status; NSM, PSM, and CSM. CSM were defined by distance of tumour ≤1 mm from the surgical margin. BCR was defined as a prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) level of >0.2 ng/mL, two values at 0.2 ng/mL, or secondary treatment for an elevated PSA level. Predictors of BCR, metastases, and mortality were analysed using Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

Of 5515 men in the SEARCH database, 4337 (79%) men met criteria for inclusion in the analysis. Of these, 2063 (48%) had NSM, 1902 (44%) had PSM, and 372 (8%) had CSM. On multivariable analysis, relative to NSM, men with CSM had a higher risk of BCR (hazard ratio [HR] 1.51, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.25–1.82; P < 0.001) but a decreased risk of BCR when compared to those men with PSM (HR 2.09, 95% CI 1.86–2.36; P < 0.001). Metastases, prostate cancer‐specific mortality and all‐cause mortality did not differ based on margin status alone.

Conclusions

Management of men with CSM is a diagnostic challenge, with a disease course that is not entirely benign. The evaluation of other known risk factors probably provides greater prognostic value for these men and may ultimately better select those who may benefit from adjuvant therapy.