Renal cell carcinoma in a setting of chronic lithium toxicity

A case of renal cell carcinoma on a background of acquired cystic disease due to chronic lithium toxicity is described. The possible pathogenetic mechanisms that may have lead to the development of the renal cell carcinoma in this setting are explored.

Authors: Zardawi, Ibrahim; Nagonkar, Santoshi; Patel, Purvish

Corresponding Author: Zardawi, Ibrahim

Lithium salts are widely used in the treatment of affective disorders of the bipolar type. Lithium is a nephrotoxic substance and patients undergoing long-term lithium treatment can present with acute lithium intoxication, chronic renal disease or nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.1,2 Lithium causes structural renal damage with tubular loss, fibrosis, inflammation, glomerular sclerosis and cyst formation.3 Cysts appear to predispose the kidney to renal cell carcinoma and an association between the two conditions has been well documented.4 A case of renal cell carcinoma on a background of acquired cystic disease due to chronic lithium toxicity is described. The possible pathogenetic mechanisms that may have lead to the development of the renal cell carcinoma in this setting are explored.

A 72 year old obese female with an 18 year history of a schizoaffective disorder, presented in March 2011 with painless haematuria. She had been on Lithium for approximately 12 years, from 1993 to 2005. She was diagnosed in 2005 with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and in 2008 with chronic kidney disease thought to be due to chronic interstitial nephritis from long term Lithium use. She has been a heavy user of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but is a non-smoker. Her past medical history included hysterectomy and appendectomy. On examination, she was found to be mildly hypertensive with a blood pressure of 155/90 mm Hg. She was haemodynamically stable with no pallor, bruising, petechiae or purpura and no signs of mucosal bleeding. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender and there were no masses or organomegaly. Her medications at presentation included Aripiprazole 10mg daily, Sodium Valproate 500mg bd, Atorvastatin 20mg daily, Thyroxin 50mcg daily and Telmisartan Hydrochlorothiazide 80/12.5 mg daily.

Investigations revealed a raised blood urea at 16.5 mmol/L (reference range (3.0-10.0 mmol/L) and serum Creatinine of 205 umol/L (reference range 30-100 umol/L). Renal ultrasound showed a mass (4.5x 4.7x 4.5 cm) with cystic and solid components and increased vascularity in the upper pole of the left kidney. No other renal masses were detected but both kidneys contained multiple cysts. A mobile echogenic mass (3.4cm X 2.8 cm in size), thought to be a blood clot, was detected in the bladder. No significant abnormalities were detected on cystoscopy and retrograde ureteroscopy, except for a blood clot which was removed during the procedure. No bladder or ureteric masses or stones were identified. Bladder biopsy showed active (acute and chronic) inflammation but no urothelial dysplasia or malignancy. A left renal tumour, indenting the renal sinus and extending into the renal vein with the presence of thrombosis was detected on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Numerous cysts, mostly less that 5mm in diameter were identified in both kidneys. There was no evidence of metastatic disease in the abdomen or pelvis. A left laparoscopic nephrectomy was performed. The patient has been well post nephrectomy with no clinical or radiological evidence of tumour recurrence.

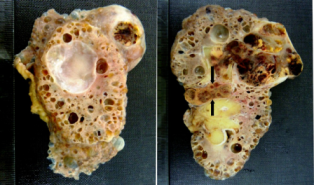

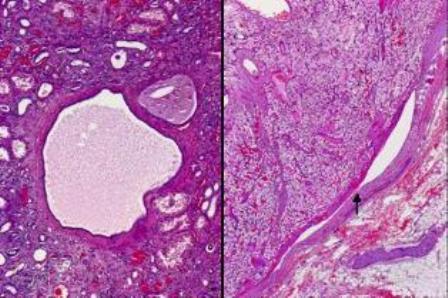

The macroscopic specimen consisted of a kidney with attached peri-nephric fat. The kidney (140x85x40mm) contained numerous cysts up to 30mm in maximum diameter (Fig. 1). A relatively circumscribed, partly necrotic tumour with haemorrhage necrosis, 60 x 55mm was noted in the upper part of the kidney with extension into the renal vein and peri-hilar fat (Fig. 1). Microscopically, the renal tumour was a Fuhrman grade 2 clear cell carcinoma. The tumour had extended into the peri-hilar adipose tissue and the renal vein. The remainder of the kidney showed numerous simple cysts, each lined with a layer of flattened cuboidal cells (Fig. 2). Cysts were present throughout the renal parenchyma with involvement of cortical and medullary tissues.

Lithium salts are widely used in the treatment of affective disorders of the bipolar type. A frequent side effect of long-standing lithium treatment is kidney damage. Compared with the general population, patients on long-term Lithium salts are 6 times more likely to develop chronic renal failure. In a recent Swedish study, plasma creatinine levels of >150 µmol/L (normal range 30-100 µmol/L) were detected in 12% of patients on long-term lithium treatment and renal replacement therapy was required in 5.3% of the lithium treated population.5 Patients undergoing long-term lithium treatment can present with acute lithium intoxication, chronic renal disease or nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.1,2 Lithium causes structural renal damage with tubular loss, fibrosis, inflammation, glomerular sclerosis and cyst formation.3,4

Cysts appear to predispose the kidney to renal cell carcinoma and an association between the two conditions has been well documented.5 The patient presented here, is obese, had been on lithium for 12 years and has misused non-steroidal anti-inflammatories for a long period of time. The above combination is important when considering renal cell carcinoma in this setting because a relationship, albeit indirect, can be established between these medications and renal cell carcinoma. Renal biopsy from patients on long-term lithium treatment often shows chronic interstitial nephritis with associated tubular atrophy, cortical and medullary fibrosis, glomerular sclerosis, tubular dilatation and cyst formation.6,7 This patient had numerous renal cysts and macroscopically these cysts were indistinguishable from the cysts of adult polycystic kidney disease. These cysts, which were deemed to be acquired (acquired cystic disease), were attributed to lithium toxicity.

Renal cell carcinoma is a group of malignancies that arise from the renal tubular epithelium. Although smoking, obesity and hypertension are the main risk factors for renal cell cancer in both sexes, exposure to environmental chemicals and prolonged intake of phenacetin-containing analgesics also play a role in the aetiology of renal cell carcinoma.8 An association between renal cell carcinoma and acquired and hereditary cysts has been well documented.9 The majority of renal neoplasms in the setting of acquired cystic kidney disease have been in patients on chronic haemodialysis for several years. Tumours also occur in patients with chronic renal failure who have not been dialysed. The number of cysts is important for establishing a diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma associated with acquired cystic disease. At least 5 cysts are necessary for a diagnosis of acquired cystic disease.8 This patient, who had not been dialysed, fulfils the criteria for acquired renal disease. Although renal tumours are found in 25% of patients with acquired cystic disease, not all lesions are histologically malignant and only 5% metastasise. This observation is different to the findings in this case, which is a high stage tumour with a large tongue of tumour extending into the main renal vein. In some cases of acquired cystic disease, atypical proliferative epithelial changes, harbouring cytogenetic abnormalities, representing early neoplastic transformation have been found. Some clear cell renal cell carcinomata arising in the setting of acquired cystic disease has been shown to have von Hipple-Lindau (VHL) gene mutations.8 The cysts in this patient are simple and there is no epithelial hyperplasia or atypia, therefore no precancerous proliferative changes are demonstrable morphologically. It is worthwhile remembering that renal cell carcinomas are rare in adult polycystic kidneys and probably occur with no more greater frequency than might be expected based on the prevalence of the two conditions.8

A small but consistent excess of renal cell carcinoma has been established with exposure to phenacetin-containing analgesics which also cause cancer of the renal pelvis.8 This patient has abused many types of analgesics for a long period of time and had often consumed large quantities of these analgesics.

The risk of renal cell carcinoma increases steadily with increasing body mass index (BMI).10 The incidence of renal cell carcinoma in obese people with a BMI of >29 kg/m2 is double that of normal individuals. In Europe one quarter of kidney cancers in both sexes are attributable to excess weight, particularly in women8. A real association would be supported by oestrogen-mediated carcinogenesis that is documented in animal models. Conversely, it could be a confounding effect of excess body weight that is often increased in women who have had many children. Our patient’s BMI is close to 30 kg/m2. The mechanism by which obesity predisposes to renal cell cancer in humans is unclear, although hormonal factors are thought to play a role. An alternative explanation is that hypertension or metabolic complications of obesity may result in kidney damage that increases susceptibility to carcinogens or promoting agents. The association with obesity persists after controlling for other risk factors, such as a history of hypertension or kidney disease and intake of meat, fat or protein.10

The incidence of renal cell carcinoma is significantly increased in people with a history of hypertension that is independent of obesity and tobacco smoking.9 The association with the use of diuretics instead is likely to be due to the associated hypertension.

Lithium is commonly used in the treatment of bipolar mental illness. It is nephrotoxic and long-term use of lithium can lead to chronic renal failure through tubular damage with cyst formation. Kidneys with multiple cysts are at risk of renal cell carcinoma. In this case, it is difficult to determine if long term Lithium use is responsible for the renal cell carcinoma as other contributing factures to renal cell carcinoma, such hypertension, obesity and analgesic abuse are also present. Despite this, patients on long-term lithium therapy should undergo regular renal function and imaging tests.

References

1. Hansen HE. Renal toxicity of lithium. Drugs 1981; 22: 461–476.

2. Timmer RT, Sands JM: Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10: 666–674.

3. Hansen HE, Hestbech J, Olsen S, Amdisen A. Renal function and renal pathology in patients with lithium-induced impairment of renal concentrating ability. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc. 1977;14:518-527.

4. Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, Aurell M. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77:219-224.

4. Hurst FP, Jindal RM, Fletcher JJ, Dharnidharka V, Gorman G, Lechner B, Nee R, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC. Incidence, predictors and associated outcomes of renal cell carcinoma in long-term dialysis patients. Urology. 2011;77:1271-1276.

6. Markovitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kammbham N, Valeri AM, Hines WH, D’Agati VD. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000; 11:1439–1448.

7. Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D, Remy P, Vincent F, Khalil A, Le Blanche AF. Chronic Lithium Nephropathy: MR Imaging for Diagnosis. Radiology 2003; 229:570–574.

8. WHO classification of tumours: Pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Edited by Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA. IARC press, Lyon 2004.

9. McCredie M, Stewart JH, Day NE. Different roles for phenacetin and paracetamol in cancer of the kidney and renal pelvis. Int J Cancer. 1993;53:245-249

10. Chow WH, McLaughlin JK, Mandel JS, Wacholder S, Niwa S, Fraumeni JF (Jr). Obesity and risk of renal cell cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1996;5:17-21.

11. Setiawan VW, Daniel O. Stram DO, Nomura AMY, Kolonel LN and Brian E. Henderson BE. Risk Factors for Renal Cell Cancer: The Multiethnic Cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007; 166: 932-940.

Figure 1. Numerous cysts in the kidney (left panel) with part of a tumour in the right upper corner of the kidney. A large haemorrhagic tumour in the upper pole of the kidney (right panel) with renal vein invasion by tumour (arrow).

Figure 2. Kidney with simple cysts, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis with mild inflammation (left panel) and clear cell renal cell carcinoma within the renal vein, as arrowed in the right panel.

Date added to bjui.org: 02/12/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-062-web