Primary small cell carcinoma of the ureter with hydronephrosis

We report a case of primary small cell carcinoma of the ureter with hydronephrosis.

Authors: Zhao Zhenhua (1), Wang Boyin (1), Yang Jianfeng (1), Wang Ning (2), Pan Shouhua (3)

1. Department of Radiology, Shaoxing People’s Hospital (Zhejiang University Shaoxing Hospital) Shaoxing, Zhejiang, China

2. Department of Pathology, Shaoxing People’s Hospital (Zhejiang University Shaoxing Hospital) Shaoxing, Zhejiang, China

3. Department of Urology, Shaoxing People’s Hospital (Zhejiang University Shaoxing Hospital) Shaoxing, Zhejiang, China

Corresponding Author: Yang Jianfeng Department of Radiology, Shaoxing People’s Hospital (Zhejiang University Shaoxing Hospital) 568 Zhongxing North Rd, Shaoxing, Zhejiang, China

Introduction

Small cell carcinoma (SCC) is usually found in the lungs, and its extrapulmonary counterpart is rarely encountered. Primary small cell carcinoma (PSCC) of the ureter with hydronephrosis is extremely rare. We report a 70-year-old woman who presented with left-sided flank pain. The clinical impression and diagnosis following renal ultrasound was of a calculus in the distal left ureter. Abdominal and pelvic CT indicated a mass near the distal ureter with pronounced hydronephrosis. The patient underwent left nephroureterectomy. Histological and immunohistochemical staining confirmed PSCC of the ureter. After 9 months, the patient was found to have massive metastases in the liver and lungs, lymphadenopathy in the retroperitoneum, and para-aortic region, and several implantation metastases in the bladder and left psoas major. Radiologists and clinicians should be aware of the possibility and severity of malignant PSCC of the ureter in patients with hydronephrosis.

Case report

A 70-year-old woman presented with left-sided flank pain without the symptoms of bladder irritation and gross hematuria. The pain was continuous with paroxysmal irritation radiating to the hypogastrium and groin. It was accompanied by nausea but no vomiting. Physical examination was unremarkable except for sensitivity to percussion in her left renal region and tenderness over the course of the left ureter. Urinalysis indicated leukocytes (+) in her urine specimen; her other laboratory data were within normal limits. Ultrasonography revealed one 6-mm diameter calculus in the distal left ureter with hydronephrosis. The pain did not improve after several days’ treatment with anti-inflammatory agents and analgesia. The patient then underwent intravenous urography (IVU), abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT), and chest radiography.

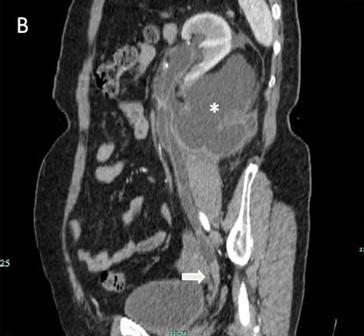

The IVU showed a left hydroureter (Fig. 1A). The CT indicated pronounced left hydronephrosis and thickened perirenal tissue within the wall of the left upper ureter. Abdominal multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) demonstrated a mass near the end of the ureter and the thickened, irregular wall of the upper ureter with pronounced hydronephrosis (Fig. 1B). We did not observe any lymphadenopathy in the pelvis, retroperitoneum, or para-aortic regions. A chest radiograph was reviewed, and no abnormality was seen.

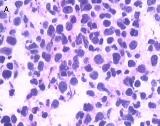

The patient underwent left nephroureterectomy. Macroscopically, a 1.6 × 1.2 × 0.5–cm grayish white lesion was identified.. Histological examination revealed that the mass was composed of small cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, round to fusiform in shape, exhibiting a high level of mitotic activity but little cytoplasm and an absence of nucleoli [Fig. 2A]. Immunohistochemical staining of the specimen was positive for chromogranin A (CgA) [Fig. 2B], CD56, synaptophysin (Syn), neuron-specific enolase, and Ki-67 80%, confirming the neuroendocrine origin of the tumor.

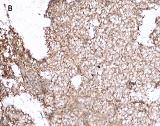

The abdominal and pelvic CT and chest radiography performed 9 months after the operation indicated massive metastases in the liver and lungs [Fig. 3A], lymphadenopathy involving the retroperitoneum, and para-aortic regions, and some implantation metastases in the bladder and left psoas major [Fig. 3B]. This patient died 10 months after operation due to multiple organ failure.

Discussion

Primary small cell carcinoma of the ureter is an extremely malignant and rare disease; only several cases worldwide have been reported so far [1-4]. To our knowledge, PSCC with hydronephrosis has never been reported. The cause of SCC of the ureter may be related to smoking, but it remains unclear [2]. There are two hypotheses regarding the histopathogenesis of urinary tract small cell carcinoma. One indicates that it originates from intrinsic neuroendocrine cells within the normal genitourinary tract derived from the neural crest during embryogenesis [5], whereas the other hypothesis suggests that it results from a transformation of pluripotent epithelial reserve cells in the genitourinary tract that exhibit the ability to generate any cell type [6]. According to Kim Ts [2], SCC of the ureter combined with other components, such as transitional cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and carcinoma sarcomatodes, supports the second hypothesis. However, in this case, there are no other components; thus, it is compatible with the first hypothesis.

Because of high mitotic activity [1, 4, 7], small cell carcinoma of the ureter usually obstructs the ureter completely. The ureter above the obstruction or renal pelvis exhibits severe dilation. To our knowledge, severe and long-standing obstruction can give rise to the renal insufficiency or renal failure; the excretion of contrast medium is then not visualized on IVU or CT after contrast administration. In this patient, we did not find these changes. We presume that this was due to the following two reasons: the pressure in the left renal pelvis decreased after the development of the hydronephrosis, and secondly that the function of the right kidney improved to compensate.

The clinical features of PSCC of the ureter are mostly hematuria and flank pain [4]. Hematuria, usually gross, is due to vascular invasion, whereas pain is secondary to hydronephrosis after obstruction of the ureter. However, in this case, the patient only presented with left-sided flank pain and radiating pain in both the hypogastrium and groin. This clinical feature was similar to the presentation of a ureteric calculus. Ultrasonography is a commonly performed examination for urogenital diseases, but its resolution is inferior to CT. We can differentiate a calculus from a mass in the ureter by CT scanning, and demonstrate the development of hydronephrosis and its relationship with surrounding tissues through MPR.

Nephroureterectomy is the primary treatment in the majority of patients with PSCC of the ureter but usually cannot achieve adequate control of the disease; cisplatin-based chemotherapy has been frequently combined with surgery, but the overall outcome is poor [1]. The lymphatics, the lung, and the liver are common metastatic sites for small cell carcinoma of the ureter, and the majority of patients with small cell carcinoma die of the disease within a year [2]. This PSCC of the ureter caused hydronephrosis, and subsequently extensive metastases involving the liver and lungs and lymphadenopathy in the retroperitoneum, and para-aortic region. A the metastasis in the psoas major muscle also occurred 9 months following the surgical procedure.

Conclusion

Primary small cell carcinoma of the ureter is rare and often misdiagnosed as a ureteric calculus or other disease. CT assisted in identifying both the lesion and subsequent metastases, but the final diagnosis depended on pathological confirmation. During operation, surgeons must be mindful of the possibility of implantation metastasis in the perirenal tissue in patients with PSCC of the ureter with hydronephrosis. Radioactive implants may be considered to help prevent metastases. A patient with an early diagnosis and comprehensive therapy may achieve a long-term relative survival

.

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

1. Kozyrakis D, Papadaniil P, Stefanakis S, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the urinary tract: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7743.

2. Kim TS, Seong DH, Ro JY. Small cell carcinoma of the ureter with squamous cell and transitional cell carcinomatous components associated with ureteral stone.J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:796-800.

3. Ishikawa S, Koyama T, Kumagai A, Takeuchi I, Ogawa D. A case of small cell carcinoma of the ureter with SIADH-like symptoms. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2004;95:725-8.

4. Kho VK, Chan PH. Primary small cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. J Chin Med Asso. 2010;73:173-6.

5. Fetissof F, Dubois MP, Lanson Y, Jobard P. Endocrine cells in renal pelvis and ureter: an immunohistochemical analysis. J Urol. 1986;135:420-1.

6. Christopher ME, Seftel AD, Sorenson K, Resnick MI. Small cell carcinoma of the genitourinary tract: an immunohistochemical, electron microscopic and clinicopathological study. J Urol.1991; 146:382-8.

7. Sved P, Gomez P, Manoharan M, Civantos F, Soloway MS. Small cell carcinoma of the bladder. BJU Int. 2004;94:12-7.

Fig 1

The IVU shows the dilated ureter (arrow) [A]. The sagittal oblique reconstruction of the left ureter shows the lesion at the end of the ureter (arrow) and hydronephrosis (asterisk) [B]

Fig 2

Light microscopy shows small cells that exhibit hyperchromatic nuclei, round to fusiform in shape, and high mitotic activity with little cytoplasm and an absence of nucleoli (H&E, 400×) [A]. The immunohistochemical staining of the specimen is positive for CgA (100×) [B]

Fig 3

Many metastases scatter over the liver [A] and one of implantation metastases are in the left psoas major (arrow) [B] 9 months postoperatively

Date added to bjui.org: 06/12/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-040-web