Papillary Cell Carcinoma in Post transplant Dialysis dependent patient – presenting as retroperitoneal hematoma

We present the case of a middle age male with ESRD with post transplant graft rejection, who presented with fever and left flank pain. Histopathology revealed a papillary cell carcinoma. Papillary cell carcinoma presenting as haemorrhage has not been previously reported in literature.

Authors: Nadeem, Mehwash; Ather, M Hammad; Sulaiman, M Nasir

Corresponding Author: Nadeem, Mehwash

For Correspondence and reprint requests

Dr Mehwash Nadeem

Dept of Surgery

Aga Khan University

P O Box 3500, Stadium Road

Karachi 74800, Pakistan

E mail drmehwash7@gmail.com

Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of the known complications of end stage renal disease (ESRD) but these patients have favourable outcome in comparison to the general population. Spontaneous bleeding in renal tumours is a rare presentation and reported only anecdotally. We present the case of a middle age male with ESRD with post transplant graft rejection, who presented with fever and left flank pain. On investigation he was found to have a left perinephric collection. Initially he was managed conservatively, but subsequently underwent surgical exploration due to persistent flank pain. At operation, he was found to have a retroperitoneal hematoma. Histopathology revealed a papillary cell carcinoma. Papillary cell carcinoma presenting as haemorrhage has not been previously reported in literature.

Key Messages

Patients with ESRD on haemodialysis (HD) have a 100 times greater risk of developing RCC so these patients should be screened annually. There should be a high index of suspicion to diagnose these tumours and more specifically identifying these tumours as a cause of haemorrhage.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in patients with dialysis dependant end stage renal disease (ESRD) is about 100 times more common than in the general population. The histopathological type and features are distinct with a clear relation to the duration that a patient has remained haemodialysis (HD) dependent. Clear cell carcinoma is the most common renal tumour in the in general population as well as in patients with ESRD, papillary cell carcinoma represents a small fraction of cases and has not previously been reported in literature to present as haemorrhage.

Case History

The patient is a 48 year old man with co morbidities of hypertension, Hepatitis C, Crohn’s disease and ESRD (on thrice weekly haemodialysis). He underwent renal transplant in 2003 after remaining on haemodialysis (HD) for one year. Four years later he had graft rejection and again become dialysis dependent. He presented complaining of a high grade intermittent fever responding to antipyretics and vague left flank pain which was non-radiating and aggravated on movement. On examination he had a blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg, pulse of 68 beats/minute and he was afebrile. On abdominal examination, there was a scar in the right iliac fossa, the graft was palpable but not tender and there was mild tenderness in the left flank. His haemoglobin was 12gm/dl with a total leukocyte count of 12.3. A non contrast enhanced CT scan (CT KUB) showed extensive fat stranding around the left kidney with an area of high density representing a collection, the corticomedullary differentiation was lost in all three kidneys and there were small calculi in the renal graft (Figure 1 and 2). The patient was admitted with a probable diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis. The possibility of drain placement was discussed, but due to multi-focality and the small size of the collection, the decision was made for conservative management. He was started on Imipenim to which his fever responded but his haemoglobin dropped to 4gm/dl without any obvious source of bleeding. His CT scan was discussed with a radiologist and they raised suspicion of small areas of haemorrhage in the left kidney rather than a collection, along with a mixed density mass in the upper pole of the right kidney which could represent a complex cyst. A contrast enhanced CT scan of his abdomen was performed which demonstrated similar findings without any evidence of ongoing bleeding. His haemoglobin stabilized at 8gm/dl after the transfusion of 2 units of packed cells but he continued to have left flank pain despite epidural analgesia. Due to persistent pain, the drop in haemoglobin and his contralateral kidney showing a solid mass highly suspicious of a cancer an elective surgical exploration was planned. Per-operatively, the patient was found to have a huge retroperitoneal hematoma on left side crossing the mid line, from which approximately 2 litres of blood clots were evacuated. The graft kidney was small and shrunken with a stone in the renal pelvis. The right kidney contained an upper pole mass. Bilateral native and graft nephrectomy was done. The patient’s post operative course was uneventful. He was discharged home on the 6th post operative day with advice on alternate day HD. Histopathology showed a papillary renal cell carcinoma in right kidney, with foci of similar tumour seen in the left kidney as well. Extensive infarct in the left kidney was seen, the margins of the graft kidney as well as the ureteric margins of both kidneys were tumour free. Since the disease was organ confined, no further treatment was given to the patient. The patient was last seen three months ago and was well.

Discussion

End stage renal disease (defined in the Framingham Study as a GFR that is < 60% of the normal level) developed in about 9% of the subjects in the Framingham Study cohort during an 18-year follow-up period(1). The data of National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys of 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2004 suggest that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease increased from 10 to 13% over the 10-year period from 1994 to 2004(2). The rate of renal replacement therapy over the 5-year observation period in a study was 1.1%, 1.3%, and 19.9%, respectively (3).

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis have more than a 100 times greater risk of RCC than age-matched healthy controls, (4-5) and the risk is considered to be progressively higher in patients with a longer duration of dialysis (6-7). A multicenter retrospective study of more than 1200 patients by Neuzillet et al has reported that RCC occurring in patients with ESRD has many favourable clinical, pathologic, and outcome features compared with those diagnosed in patients from the general population. In the ESRD group, RCC occurred in younger patients (55+/-12 yrs vs. 62+/-12 yrs; p < 0.0001) and more often in male patients (3.2 men vs.1.6 women; p < 0.0001). Tumours were more frequently discovered incidentally in the ESRD group (87% vs.44%; p < 0.0001) (8). In this series, the incidental RCC diagnosis rate was in 87% compared with 44% in the general population. Such a high rate (75-100%) of incidental diagnosis had already been reported (9-10). This may be due to either to the constitutional low aggressiveness of ESRD tumours, related in part to their favourable histological phenotype, or to early diagnosis of renal tumours in the ESRD setting (due to screening) (8).

The spectrum of histological types of RCC arising in ESRD is distinct from that of sporadic RCC. Tumours arising in the setting of ESRD show microscopic features that are either similar to sporadic cases (clear cell, papillary and chromophobe RCC) or unique to ESRD, including acquired cystic disease (ACD)-associated RCC, and clear cell-papillary RCC (11). Clear cell carcinomas are less frequent (59% vs. 89%) and papillary carcinomas are more frequent (37%) than in the general population (7%) but with clear cell still being the most common (8).

A spontaneous retroperitoneal haemorrhage (SRH) is defined as a retroperitoneal haemorrhage that occurs without proceeding trauma or any underlying pathology. The majority of the patients respond to conservative treatment, with stopping of the offending agent (anticoagulants), judicious resuscitation with fluids and blood products and other supportive care. Surgery or radiological intervention is performed if there is evidence of continued bleeding, but these two modalities have some disadvantages. Spontaneous rupture of a renal neoplasm is a rare entity. Most commonly reported are angiomyolipomas. Other renal tumours reported in literature presenting as retroperitoneal hematoma are leiomyosarcoma (12-13) and metastatic gestational trophoblastic tumour (14). Papillary cell carcinoma of renal origin has not yet been reported in the literature presenting as retroperitoneal hematoma.

In our patient triple nephrectomy was dictated by three different indications. The left kidney was removed because it was the source of pain, bleeding and relative hemodynamic instability, the right kidney was removed as it was harbouring a solid mass suspicious of malignancy and the graft was removed as it had been rejected and also contained a calculus.

Conclusion

Annual screening of patients with ESRD should be done for RCC and ACKD. Although spontaneous rupture of renal neoplasm is a rare entity, there should be a high index of suspicion for bleeding when patients with ESRD present with flank pain in order to avoid a fatal outcome. Presentation of papillary cell carcinoma as a ruptured renal neoplasm has not been reported in literature as yet.

Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of the known complications of end stage renal disease (ESRD) but these patients have favourable outcome in comparison to the general population. Spontaneous bleeding in renal tumours is a rare presentation and reported only anecdotally. We present the case of a middle age male with ESRD with post transplant graft rejection, who presented with fever and left flank pain. On investigation he was found to have a left perinephric collection. Initially he was managed conservatively, but subsequently underwent surgical exploration due to persistent flank pain. At operation, he was found to have a retroperitoneal hematoma. Histopathology revealed a papillary cell carcinoma. Papillary cell carcinoma presenting as haemorrhage has not been previously reported in literature.

Key Messages

Patients with ESRD on haemodialysis (HD) have a 100 times greater risk of developing RCC so these patients should be screened annually. There should be a high index of suspicion to diagnose these tumours and more specifically identifying these tumours as a cause of haemorrhage.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in patients with dialysis dependant end stage renal disease (ESRD) is about 100 times more common than in the general population. The histopathological type and features are distinct with a clear relation to the duration that a patient has remained haemodialysis (HD) dependent. Clear cell carcinoma is the most common renal tumour in the in general population as well as in patients with ESRD, papillary cell carcinoma represents a small fraction of cases and has not previously been reported in literature to present as haemorrhage.

Case History

The patient is a 48 year old man with co morbidities of hypertension, Hepatitis C, Crohn’s disease and ESRD (on thrice weekly haemodialysis). He underwent renal transplant in 2003 after remaining on haemodialysis (HD) for one year. Four years later he had graft rejection and again become dialysis dependent. He presented complaining of a high grade intermittent fever responding to antipyretics and vague left flank pain which was non-radiating and aggravated on movement. On examination he had a blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg, pulse of 68 beats/minute and he was afebrile. On abdominal examination, there was a scar in the right iliac fossa, the graft was palpable but not tender and there was mild tenderness in the left flank. His haemoglobin was 12gm/dl with a total leukocyte count of 12.3. A non contrast enhanced CT scan (CT KUB) showed extensive fat stranding around the left kidney with an area of high density representing a collection, the corticomedullary differentiation was lost in all three kidneys and there were small calculi in the renal graft (Figure 1 and 2). The patient was admitted with a probable diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis. The possibility of drain placement was discussed, but due to multi-focality and the small size of the collection, the decision was made for conservative management. He was started on Imipenim to which his fever responded but his haemoglobin dropped to 4gm/dl without any obvious source of bleeding. His CT scan was discussed with a radiologist and they raised suspicion of small areas of haemorrhage in the left kidney rather than a collection, along with a mixed density mass in the upper pole of the right kidney which could represent a complex cyst. A contrast enhanced CT scan of his abdomen was performed which demonstrated similar findings without any evidence of ongoing bleeding. His haemoglobin stabilized at 8gm/dl after the transfusion of 2 units of packed cells but he continued to have left flank pain despite epidural analgesia. Due to persistent pain, the drop in haemoglobin and his contralateral kidney showing a solid mass highly suspicious of a cancer an elective surgical exploration was planned. Per-operatively, the patient was found to have a huge retroperitoneal hematoma on left side crossing the mid line, from which approximately 2 litres of blood clots were evacuated. The graft kidney was small and shrunken with a stone in the renal pelvis. The right kidney contained an upper pole mass. Bilateral native and graft nephrectomy was done. The patient’s post operative course was uneventful. He was discharged home on the 6th post operative day with advice on alternate day HD. Histopathology showed a papillary renal cell carcinoma in right kidney, with foci of similar tumour seen in the left kidney as well. Extensive infarct in the left kidney was seen, the margins of the graft kidney as well as the ureteric margins of both kidneys were tumour free. Since the disease was organ confined, no further treatment was given to the patient. The patient was last seen three months ago and was well.

Discussion

End stage renal disease (defined in the Framingham Study as a GFR that is < 60% of the normal level) developed in about 9% of the subjects in the Framingham Study cohort during an 18-year follow-up period(1). The data of National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys of 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2004 suggest that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease increased from 10 to 13% over the 10-year period from 1994 to 2004(2). The rate of renal replacement therapy over the 5-year observation period in a study was 1.1%, 1.3%, and 19.9%, respectively (3).

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis have more than a 100 times greater risk of RCC than age-matched healthy controls, (4-5) and the risk is considered to be progressively higher in patients with a longer duration of dialysis (6-7). A multicenter retrospective study of more than 1200 patients by Neuzillet et al has reported that RCC occurring in patients with ESRD has many favourable clinical, pathologic, and outcome features compared with those diagnosed in patients from the general population. In the ESRD group, RCC occurred in younger patients (55+/-12 yrs vs. 62+/-12 yrs; p < 0.0001) and more often in male patients (3.2 men vs.1.6 women; p < 0.0001). Tumours were more frequently discovered incidentally in the ESRD group (87% vs.44%; p < 0.0001) (8). In this series, the incidental RCC diagnosis rate was in 87% compared with 44% in the general population. Such a high rate (75-100%) of incidental diagnosis had already been reported (9-10). This may be due to either to the constitutional low aggressiveness of ESRD tumours, related in part to their favourable histological phenotype, or to early diagnosis of renal tumours in the ESRD setting (due to screening) (8).

The spectrum of histological types of RCC arising in ESRD is distinct from that of sporadic RCC. Tumours arising in the setting of ESRD show microscopic features that are either similar to sporadic cases (clear cell, papillary and chromophobe RCC) or unique to ESRD, including acquired cystic disease (ACD)-associated RCC, and clear cell-papillary RCC (11). Clear cell carcinomas are less frequent (59% vs. 89%) and papillary carcinomas are more frequent (37%) than in the general population (7%) but with clear cell still being the most common (8).

A spontaneous retroperitoneal haemorrhage (SRH) is defined as a retroperitoneal haemorrhage that occurs without proceeding trauma or any underlying pathology. The majority of the patients respond to conservative treatment, with stopping of the offending agent (anticoagulants), judicious resuscitation with fluids and blood products and other supportive care. Surgery or radiological intervention is performed if there is evidence of continued bleeding, but these two modalities have some disadvantages. Spontaneous rupture of a renal neoplasm is a rare entity. Most commonly reported are angiomyolipomas. Other renal tumours reported in literature presenting as retroperitoneal hematoma are leiomyosarcoma (12-13) and metastatic gestational trophoblastic tumour (14). Papillary cell carcinoma of renal origin has not yet been reported in the literature presenting as retroperitoneal hematoma.

In our patient triple nephrectomy was dictated by three different indications. The left kidney was removed because it was the source of pain, bleeding and relative hemodynamic instability, the right kidney was removed as it was harbouring a solid mass suspicious of malignancy and the graft was removed as it had been rejected and also contained a calculus.

Conclusion

Annual screening of patients with ESRD should be done for RCC and ACKD. Although spontaneous rupture of renal neoplasm is a rare entity, there should be a high index of suspicion for bleeding when patients with ESRD present with flank pain in order to avoid a fatal outcome. Presentation of papillary cell carcinoma as a ruptured renal neoplasm has not been reported in literature as yet.

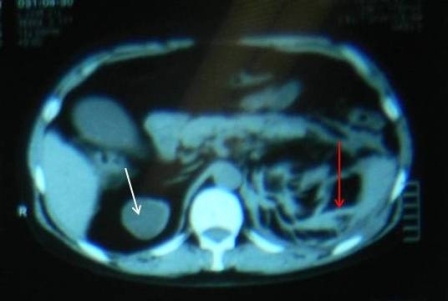

Figure 1: white arrow showing mixed density mass and red arrow showing extensive perinephric stranding

Figure 2: Image of right upper pole mixed density mass. Arrow showing area of collection around left kidney References:

References

1. Fox CS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Culleton B, Wilson PW, Levy D. Predictors of new-onset kidney disease in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004 Feb 18;291(7):844-50.

2. Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007 Nov 7;298(17):2038-47.

3. Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH. Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Mar 22;164(6):659-63.

4. Choyke PL. Acquired cystic kidney disease. Eur Radiol. 2000;10(11):1716-21.

5. Hora M, Hes O, Reischig T, Urge T, Klecka J, Ferda J, et al. Tumours in end-stage kidney. Transplant Proc. 2008 Dec;40(10):3354-8.

6. Vamvakas S, Bahner U, Heidland A. Cancer in end-stage renal disease: potential factors involved -editorial. Am J Nephrol. 1998;18(2):89-95.

7. Peces R. Malignancy and chronic renal failure. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2003 Jan-Mar;14(1):5-14.

8. Neuzillet Y, Tillou X, Mathieu R, Long JA, Gigante M, Paparel P, et al. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in patients with end-stage renal disease exhibits many favourable clinical, pathologic, and outcome features compared with RCC in the general population. Eur Urol. 2011 Aug;60(2):366-73.

9. Kojima Y, Takahara S, Miyake O, Nonomura N, Morimoto A, Mori H. Renal cell carcinoma in dialysis patients: a single center experience. Int J Urol. 2006 Aug;13(8):1045-8.

10. Neuzillet Y, Lay F, Luccioni A, Daniel L, Berland Y, Coulange C, et al. De novo renal cell carcinoma of native kidney in renal transplant recipients. Cancer. 2005 Jan 15;103(2):251-7.

11. Tickoo SK, dePeralta-Venturina MN, Harik LR, Worcester HD, Salama ME, Young AN, et al. Spectrum of epithelial neoplasms in end-stage renal disease: an experience from 66 tumor-bearing kidneys with emphasis on histologic patterns distinct from those in sporadic adult renal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006 Feb;30(2):141-53.

12. Grasso M, Blanco S, Fortuna F, Crippa S, Di Bella C. Spontaneous rupture of renal leiomyosarcoma in a 45-year-old woman. Arch Esp Urol. 2004 Oct;57(8):870-2.

13. Moazzam M, Ather MH, Hussainy AS. Leiomyosarcoma presenting as a spontaneously ruptured renal tumor-case report. BMC Urol. 2002 Nov 19;2:13.

14. Vijay RK, Kaduthodil MJ, Bottomley JR, Abdi S. Metastatic gestational trophoblastic tumour presenting as spontaneous subcapsular renal haematoma. Br J Radiol. 2008 Sep;81(969):e234-7

Date added to bjui.org: 09/10/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-050-web