Massive urinary tract haemorrhage following bladder decompression by urethral catheterisation

The development of haematuria following bladder decompression is a well described phenomenon, but is usually transient, mild, and of little clinical consequence. We describe a case in which bladder decompression precipitated massive urinary tract haemorrhage requiring multiple blood transfusions and bilateral nephrostomy insertion

Authors: Spencer Chapman, Michael; Harber, Mark

Department of Nephrology, Royal Free Hampstead NHS Trust, London, UK

Corresponding Author: Spencer Chapman, Michael

Introduction

Urinary retention is a frequently encountered problem in everyday clinical practice. When chronic, the patient is able to urinate and may be asymptomatic, or may complain of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as urinary frequency, urgency or hesitancy, poor urinary stream, post-micturition dribbling, nocturia or urinary incontinence. However the urinary tract is often subjected to high pressures which are required to allow voiding. Over time high pressures may damage the entire urinary tract: obstructive nephropathy resulting in renal failure and bladder changes such wall thickening, trabeculation, and loss of capillary and tissue integrity(1). The immediate management of urinary retention is urethral catheterisation to allow free drainage of urine from the bladder. The development of haematuria following bladder decompression is a well described phenomenon, but is usually transient, mild, and of little clinical consequence. We describe a case in which bladder decompression precipitated massive urinary tract haemorrhage requiring multiple blood transfusions and bilateral nephrostomy insertion.

Case report

A 58 year-old Caucasian man was transferred to our unit from a local hospital with massive urinary tract haemorrhage and renal failure.

He had presented to his GP five days previously complaining of dysuria. He was prescribed a course of antibiotics for a presumed urinary tract infection and blood taken for a full blood count and urea and electrolyte estimation. The results of his blood tests demonstrated a creatinine level of 958 μmol/l and haemoglobin of 5.2 g/dL. He was referred immediately to his local Accident & Emergency (A&E) department.

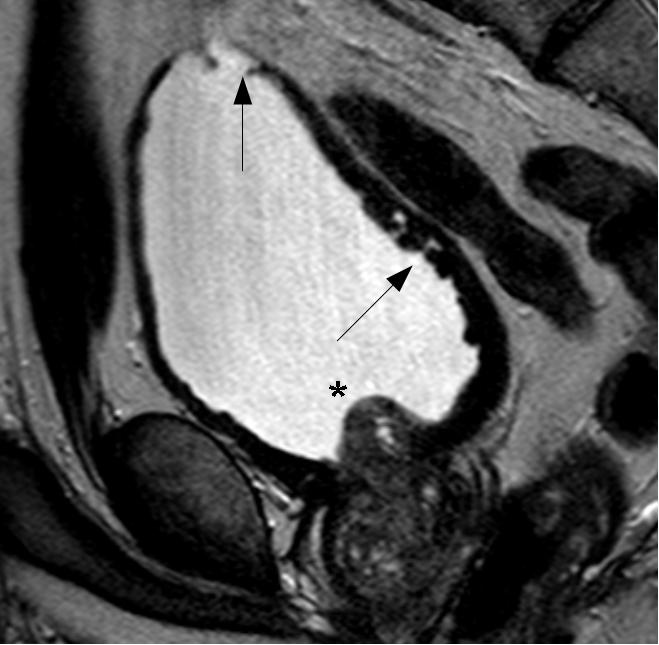

At his local A&E, he reported prostatic symptoms of urinary frequency, poor stream and nocturia. These had been present for the last twenty years but had worsened over the previous few weeks. The symptoms were accompanied by general lethargy, malaise and aching thoraco-lumbar back pain that radiated to his groin. In addition he had recently noticed bilateral numbness and dysaesthesiae in his fingertips. His past medical history was notable only for long-standing prostatic symptoms for which he had been investigated three years previously, at which time a serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was measured at 5.4 μg/L. MRI of the prostate had showed an enlarged central lobe of the prostate and bladder changes consistent with chronic obstruction, but no evidence of malignancy (Figure 1a and Figure 1b). He had undergone urethroscopy and cystoscopy which were reportedly normal and he did not undergo any surgical intervention. He had been lost to follow up. There was no history of neurological disease. His medications included losartan, doxazosin and simvastatin. He reported no prescription or over-the-counter use of aspirin, clopidogrel or other anticoagulants. He had a 30 pack year smoking history, drank around 5 units of alcohol a week and did not use illicit drugs. He was afebrile and observations were within normal limits. General examination was reportedly unremarkable.

Initial blood tests showed a creatinine of 958 μmol/L, urea of 43.3 mmol/L, haemoglobin of 5.2 g/dL, corrected calcium of 2.06 mmol/L, phosphate of 3.29 mmol/L, and potassium of 5.8 mmol/L.

He was transfused and a urethral catheter was easily inserted which immediately drained 2.9L of clear urine. After a few hours the urine was noted to have become a pale red colour. Overnight this progressed to frank haematuria with clots. This persisted, and over the following 3 days he underwent bladder irrigation and required transfusion with 10 units of packed red blood cells, 7 units of fresh frozen plasma and 1 unit of platelets.

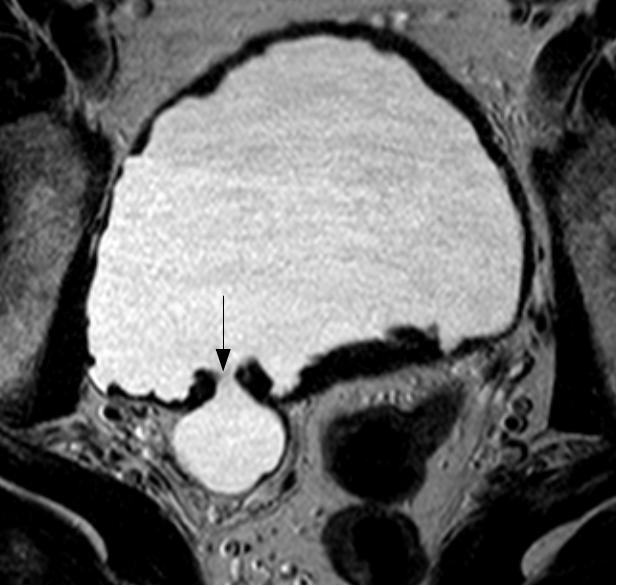

The patient’s haematuria and renal failure continued and on the fifth hospital day he was transferred to our unit. His haemoglobin was measured at 5.8 g/dL, urea 37.2 mmol/L, and creatinine 809 μmol/L. Bladder irrigation was continued and he was further transfused. CT of the abdomen and pelvis obtained with the administration of contrast material revealed hugely dilated renal pelvises bilaterally, measuring 10cm in maximal diameter on the right and 7cm on the left (Figure 2a). The catheterised bladder was diffusely thick-walled with a posterior diverticulum (Figure 2b). High attenuation material likely to represent haemorrhage was present throughout the bladder, ureters and renal pelvises. Both kidneys were hydronephrotic. No focal lesion or active bleeding was identified.

At this stage there was considerable discussion regarding the benefits of bilateral nephrostomy insertion to relieve back pressure on his kidneys. Renal failure was persisting with the need for dialysis under consideration, and imaging suggested obstruction at the level of the ureters due to insoluble blood clot. A consensus was reached that nephrostomy insertion would be likely to hasten renal recovery and potentially avoid the need for dialysis. On the eighth hospital day he underwent bilateral nephrostomy insertion. Serum creatinine levels fell and dialysis was not required.

Over the next two weeks he underwent bilateral antegrade stenting of his ureters, and by the twenty-fifth hospital day, both nephrostomies were removed. Shortly after he was discharged with a urethral catheter and right ureteric JJ stent in situ. His creatinine on discharge was 348 μmol/L. Two months later, at which time his creatinine was 241 μmol/L, he underwent successful transurethral resection of the prostate. Notably, no false passage was seen in the urethra. His LUTS were much improved and the urethral catheter was no longer required. He went on to have laparoscopic pyeloplasty of the right kidney and removal of the right JJ stent. Radioisotope renography with MAG-3 performed one month later demonstrated reasonable bladder emptying post-micturition, normal transit times, no evidence of obstruction, but ongoing dilatation of the right renal pelvis.

Discussion

Urinary retention is the inability to empty the bladder. When chronic, the patient is able to pass urine, but may experience voiding difficulties and bladder emptying is incomplete. The usual cause is bladder outlet obstruction, the aetiology of which may be enlargement of the prostate (benign or malignant), drugs (e.g. anticholinergics, antispasmodics), congenital deformities (e.g. meatal stenosis, posterior urethral valves) or urethral strictures (from trauma or infection). It largely affects men from middle-age onwards reflecting the increasing incidence of benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) in this group. Women are also affected however, around 50% of women are diagnosed with Fowler’s syndrome: a problem of inadequate urethral sphincter relaxation (2).

In order to facilitate emptying, the bladder is forced to hypertrophy so as to increase its contractile force. This results in bladder wall thickening, trabeculation and friability. It may also become increasingly sensitive (contributing to symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency and incontinence) and eventually become weakened thereby preventing complete bladder emptying. The structural changes within the bladder are thought to affect the integrity of capillaries and tissues within its wall.

Haematuria following bladder decompression by urethral catheterisation is well-recognized, and visible haematuria is estimated to occur in 2-16% of patients(3). However, though there are case reports of clinically significant haematuria, they are rare and we could find no reports in the literature of haemorrhage requiring multiple blood transfusions as in this case (4). Factors contributing to the severity of bleeding in this case include the significant structural damage to the urinary tract resulting from many years of urinary retention, and possible coagulopathy that is part of the “uraemic syndrome” associated with renal failure. Traditional teaching recommends a “clamping technique” to achieve step-wise gradual bladder decompression and supposedly reduce the risk of haematuria. Use of an IV giving set to achieve gradual decompression has also been advocated (5). However, these approaches are time consuming and presently there is scant evidence to support their use (8). We could find no randomized studies comparing gradual bladder decompression with quick, complete emptying, and other studies suggest that the risk of haematuria correlates with the severity of bladder wall damage prior to catheterisation, and not the rate of initial emptying (6). Furthermore, studies of changes in intravesical pressure following catheterisation for acute urinary retention show that the pressure drops to around 50% of the initial value after drainage of only 100mL (7)– hence clamping after 1000mL (a commonly adopted figure) might not be expected to significantly reduce risk of bleeding.

One question brought up by this case is whether the haemorrhage responsible for decompression haematuria is confined to the bladder, or if it occurs throughout the urinary tract. In our patient blood clot was seen to fill and distend both renal pelvises; did this blood track up from the bladder or did it originate from bleeding within the pelvis itself? A number of factors lead us to conjecture that the bleeding may well have originated from the wall of the renal pelvis itself. Firstly, the renal pelvises were filled with large volumes of clot in the absence of significant dilatation of the ureters (images not shown). Secondly, there is no reason to believe that the pathological process resulting from chronic urinary retention affecting the integrity of capillaries should be limited to the bladder. In the absence of a competent uretero-vesical valve, the ureters and collecting system of the kidneys are subjected to similarly high pressures and are likely to undergo similar pathological changes.

Given this, what can be done to minimise harm to the patient when considering urethral catheterisation for urinary retention? Most importantly, one must recognize patients who are at risk of clinically significant decompression haematuria. Risk correlates with the chronicity of symptoms and the degree of bladder wall damage. Hence, patients such as ours with a long history of LUTS are at increased risk and should have close monitoring post-catheterisation. It is currently unclear as to whether strategies facilitating “gradual decompression” should be advocated: further studies are required to assess the effectiveness and practicality of such strategies.

Teaching points

- Chronic urinary retention should be suspected in patients with a dilated upper urinary tract and/ or a history of lower urinary tract symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, hesitancy, straining, incomplete bladder emptying, poor flow and dribbling.

- “Decompression haematuria” can commonly occur following urethral catheterisation, and is the result of the sudden drop of pressure in a damaged bladder.

- Rarely, such bleeding may be severe and require blood transfusion – therefore close monitoring is required in at-risk patient groups.

Fig. 1a

Fig. 1b

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2b

References

1. High pressure chronic retention. George NJ, O’Reilly PH, Barnard RJ, Blacklock NJ. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983 Jun 4;286(6380):1780-3.

2. Urinary retention in women: its causes and management. Kavia RB, Datta SN, Dasgupta R, et al; BJU Int. 2006 Feb;97(2):281-7.

3. Management of urinary retention: rapid versus gradual decompression and risk of complications. Nyman MA, Schwenk NM, Silverstein MD . Mayo Clin Proc. 1997 Oct;72(10):951-6.

4. Hematuria as a complication of sudden decompression of chronically distended bladder in a child with neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Soylu A, Kavukçu S, Türkmen M, Arici A, Aktud T. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000 Jun;16(3):221.

5. Slow decompression of the bladder using an intravenous giving set. Perry A, Maharaj D, Ramdass MJ, Naraynsingh V. Int J Clin Pract. 2002 Oct;56(8):619.

6. Comparison of rapid versus slow decompression of the distended urinary bladder. Gould F, Cheng CY, Lapides J. Invest Urol. 1976 Sep;14(2):156-8.

7. Intravesical pressure changes during bladder drainage in patients with acute urinary retention. Christensen J, Ostri P, Frimodt-Møller C, Juul C. Urol Int. 1987;42(3):181-4.

8. Practical management of patients with dilated upper tracts and chronic retention of urine. George NJ, O’Reilly PH, Barnard RJ, Blacklock NJ. Br J Urol. 1984 Feb;56(1):9-12.

Date added to bjui.org: 11/12/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-092-web