Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as vesicovaginal fistula

This is a previously unreported presentation of Hodgkin’s lymphoma within the context of what is itself a rare complication of neglected pessary use.

Authors:

Megan Murdocha;Paul Hiltonb

a) Clinical Research Associate, Newcastle University and Specialist Registrar in Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Northern Deanery

b) Consultant Gynaecologist & Urogynaecologist, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Corresponding Author: Paul Hilton, Consultant Gynaecologist & Urogynaecologist, Directorate of Women’s Services, Level 5, Leazes Wing Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne , NE1 4LP, UK. Email: paul.hilton@ncl.ac.uk

Introduction

We report the case of a 79-year-old female who presented with acute onset urinary incontinence following the use of a shelf pessary in the management of her vaginal prolapse. Examination revealed a large vesicovaginal fistula of unusual appearance; subsequent biopsy of the adjacent vaginal tissue confirmed classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma of mixed cellularity type. This is a previously unreported presentation of Hodgkin’s lymphoma within the context of what is itself a rare complication of neglected pessary use.

Case report

The patient underwent abdominal hysterectomy in her forties and required a subsequent vaginal procedure for prolapse symptoms in her early seventies; as far as can be ascertained this was a conventional prolapse repair, without incorporation of an non-absorbable ‘mesh’ materials. She developed recurrent prolapse shortly after surgery and this was managed with a shelf pessary. Her symptoms were so well controlled that she did not attend for further follow-up, and the pessary was left in situ for 7 years without review.

Her past history included osteoporosis and hypertension; her medication at presentation was alendronate (once weekly), calcium carbonate (calcichew) (once daily) and amlodopine (5mg daily). She had left hip and left shoulder replacements.

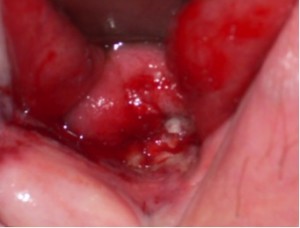

She presented with sudden onset of continuous urinary incontinence having not had any urinary symptoms previously. There were no reported bowel symptoms. On examination under anaesthesia the shelf pessary was embedded in the anterior vaginal wall; after removal a 4x5cm vesicovaginal fistula was found extending from the vaginal vault to the level of the mid trigone. There was third degree prolapse of the vaginal vault. An intravenous urogram showed no evidence of ureteric obstruction. An indwelling urethral catheter was inserted and left on free drainage for one month to encourage spontaneous closure. This made no difference to her symptoms and she was referred to a tertiary urogynaecology unit specialising in fistula repair. Examination under anaesthesia was repeated in order to plan the route and method of repair. This revealed a hard necrotic area at the posterior edge of the fistula. There was no extension into the rectum. (Figure 1a, b & c)

Figure 1a. Initial view on examination showing prolapse of the bladder wall through the fistula.

1b. Posterior edge of fistula with Allis tissue forceps on the vaginal wall around the fistula edges, and a Landon blade retracting the prolapsed bladder wall.

1c. Close-up view as in figure 1b.

Provisional histology suggested changes secondary to chronic inflammation (consistent with her long-term pessary use), but also raised the possibility of lymphoma. After discussion it was felt appropriate to proceed with surgery as planned, and vaginal vesicovaginal fistula repair combined with repair of the prolapse was undertaken by colpocleisis incorporating a Martius bulbocavernosus muscle & fat graft from the left labium majus; the ureters were stented during the procedure, and all residual visibly abnormal tissue in the area of the fistula was excised.

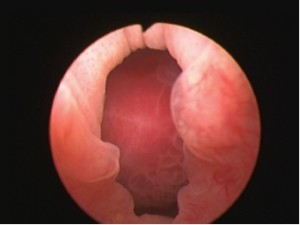

Figure 2a. Cystoscopic appearance of fistula.

Subsequent histology of the excised tissues was felt to represent an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) -positive lymphoproliferative disease (LPD), consistent with either ‘LPD in the context of chronic inflammation in an elderly person’ or with a mixed cellularity type of classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (MCCHL). The clinical, radiological and histological findings were discussed at two independent specialist haematology/lymphoma MDT groups and the final agreed diagnosis, based on the finding of Reed-Sternberg cells, was of MCCHL.

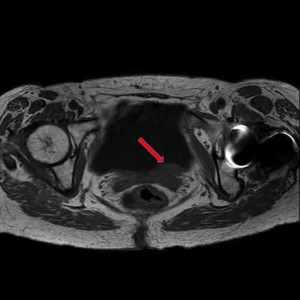

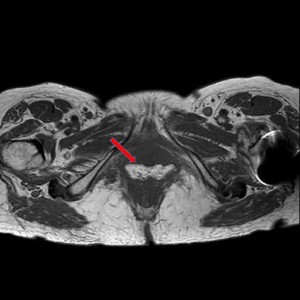

After discharge from the urogynaecology unit, she was referred to her local haematologist for further imaging and clinical review. CT images were difficult to interpret in view of the recent surgery, prior hysterectomy and a left total hip replacement. MRI scan of the pelvis showed a small thickened area of tissue between the rectum and the left side of the bladder, i.e. in the area of the recent surgery, and above the level of the Martius fat graft (see figure 3 a & b).

Figure 3. MRI images at 3 months postoperative: 3a showing thickened area to left of bladder base (arrowed).

3b. showing the Martius labial fat graft passing from left labium majus into the lower vagina (arrowed).

Whilst it was not possible to establish with certainty whether this represented postoperative fibrosis or residual disease, it was felt appropriate to consider this as stage 1AE classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Conventional treatment would have included ABVD chemotherapy (adiamycin, bleomycin, vincristine, dacarbazine) plus involved-field radiotherapy. However, in a patient of almost 80 years of age, with at worst minimal residual disease, and in the absence of evidence of nodal or distant disease, it was decided to treat with radiotherapy alone. The patient received external beam radiotherapy to the upper vagina in a dose of 30Gy in 15 fractions. At subsequent review she was free from symptoms, signs or MRI evidence of disease progression; she remains under 6-monthly surveillance. Urogynaecology review confirmed a successful fistula and prolapse repair and she has been discharged from follow up.

Discussion

In the UK, fistulae of the female genital tract are uncommon; a recent review of Hospital Episode Statistics suggest that around 120 urogenital fistulae are treated surgically each year.1 The use of mechanical devices (vaginal pessaries) in the management of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is common. Generally they are used for women who have not completed their family or those who do not wish to proceed to surgery, or are considered unsuitable for surgery. Fistula as a result of pessary use has been reported, but is unusual. A review in 2008 identified 39 major complications associated with pessary use, including eight vesicovaginal fistulas and four rectovaginal fistulas.2 Since the number of women treated by pessary for prolapse is unknown, the ‘fistula risk’ associated with this form of treatment cannot be determined. In a recent case series of urogenital fistula in the UK, 11/348 (3.2%) were associated with the use of pessaries for the conservative management of POP.3

In 2008 there were 1730 new cases of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the UK. The incidence in females is 2.4 per 100,000; in women two peaks occur at the ages of 20-24 and 70-74 years.4 Extra-nodal lymphoma (with the primary disease other than in lymph nodes) may present at any site, and rare cases in the female genital tract have been reported.5, 6 It is said that 25% of malignant lymphomas arise at extra-nodal sites and in only 1% of women with extra-nodal tumours is the genital tract involved.5 This would suggest an incidence of primary genital tract Hodgkin’s of less than 1 per 100,000,000/ year . The World Health Organisation classification divides Hodgkin’s lymphoma into several pathologic subtypes.7 In 15% the picture is described as classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma of mixed cellularity subtype, as in this case.4 The aetiology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma is unknown but studies have suggested a viral link; 50% of classical Hodgkin’s lymphomas overall, and up to 70% of MCCHL are EBV-positive.8 There is a known association between chronic inflammation and cancer and it is suggested that chronic inflammation triggered by EBV has a role in the aetiology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.9 In the case presented, the possibility that this arose because of the presence of inflammation related to the long neglected vaginal pessary must be considered.

Conventionally it is recommended that vaginal pessaries are removed and the vagina examined for erosions on a regular basis. This is often undertaken every 4-6 months although the optimum frequency has not been established and there is no consensus on the interval between pessary changes.10 The authors of the most recent Cochrane review of mechanical devices in the management of pelvic organ prolapse concluded that randomised controlled trials are needed to inform the best ways to manage long-term pessary use.10

Conclusion

A case of classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as a vesicovaginal fistula in a neglected vaginal pessary user is presented. Although this is an extremely rare complication of pessary use, it emphasises the importance of regular review, including pessary removal, bimanual examination, and speculum visualisation of the vaginal walls. With an increasing move to pessary management in primary care by General Practitioners and Practice Nurses, the development and implementation of an appropriate educational package is important.

References

1. Cromwell D, Hilton P. Patterns of care and outcomes of surgical treatment for urogenital fistula among English NHS hospitals between 2000 and 2009. 2012:(submitted).

2. Arias BE, Ridgeway B, Barber MD. Complications of neglected vaginal pessaries: case presentation and literature review. Int Urogynecol J & Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(8):1173-738.

3. Hilton P. Urogenital fistula in the UK – a personal case series managed over 25 years. BJU Int. 2011:(early view).

4. CancerHelp UK. Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. 2012; Available from: https://cancerhelp.cancerresearchuk.org/type/hodgkins-lymphoma/

5. Cheong IJ, Kim SH, Park CM. Primary Uterine Lymphoma: A Case Report. Korean Journal of Radiology. 2000;1(4):223-5.

6. Raggio ML, Bostrom SG, Harden EA. Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the uterus presenting as a refractory pelvic inflammatory disease. A case report. J Repro Med. 1988;33(10):827-30.

7. Swerdlow S. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. ; 2008.

8. Thomas RK, Re D, Zander T, Wolf J, Diehl V. Epidemiology and etiology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Annals of Oncology. 2002;13(suppl. 4):147-52.

9. Khan GG. Epstein-Barr virus, cytokines, and inflammation: A cocktail for the pathogenesis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma? Experimental Hematology. 2006;34(4):399-406.

10. Adams EJ, Thomson AJM, Maher C, Hagen S. Mechanical devices for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;Issue 2:Art. No.: CD004010.

Date added to bjui.org: 07/06/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-017-web