Editorial: Cognitive training and assessment in robotic surgery – is it effective?

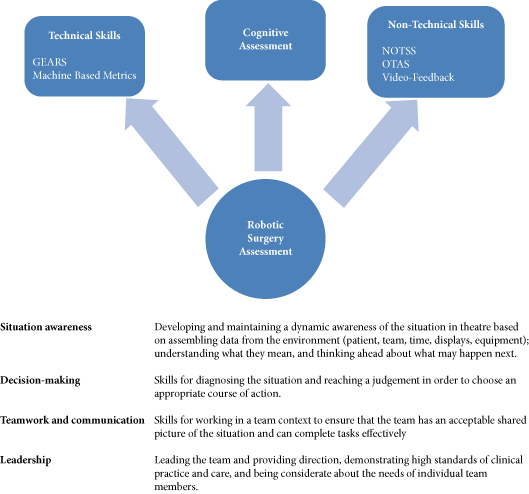

A formal and standardised process of credentialing and certification is required that should not merely be based on the number of completed cases but should be done via demonstration of proficiency and safety in robotic procedural skills. Therefore, validated assessment tools for technical and non-technical skills are required. In addition to effective technical skills, non-technical skills are vital for safe operative practice. These skill-sets can be divided into three categories; social (communication, leadership and teamwork), cognitive (decision making, planning and situation awareness) and personal resource factors (ability to cope with stress and fatigue) [1] (Fig. 1). Robotic surgeons are not exempt in requiring these skills, as situation awareness for example may become of even more significance with the surgeon placed at a distance from the patient. Most of these skills can, just like technical skills, be trained and assessed.

Various assessment tools have been developed, e.g. the Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons (NOTSS) rating system [1] that provides useful insight into individual non-technical skill performance. The Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery (OTAS) rating scale has additionally been developed and is suited better for operative team assessment [2]. Decision-making (cognitive skill) is considered as one of the advanced sets of skills and it consolidates exponentially with increasing clinical experience [3]. A structured method for this sub-set of skills training and assessment does not exist.

The present paper by Guru et al. [4] discusses an interesting objective method to evaluate robot-assisted surgical proficiency of surgeons at different levels. The paper discusses the use of utilising cognitive assessment tools to define skill levels. This incorporates cognitive engagement, mental workload, and mental state. The authors have concluded from the results that cognitive assessment offers a more effective method of differentiation of ability between beginners, competent and proficient, and expert surgeons than previously used objective methods, e.g. machine-based metrics.

Despite positive results, we think that further investigation is required before using cognitive tools for assessment reliably. Numbers were limited to 10 participants in the conducted study, with only two participants classified into the beginner cohort. This provides a limited cross-section of the demographic and further expansion of the remaining competent and proficient and expert cohorts used would be desirable. Furthermore, whilst cognitive assessment has the potential as a useful assessment tool, utility within training of surgeons is not discussed at present. Currently cognitive assessment shows at what stage a performer is within his development of acquiring technical skills; however, it does not offer the opportunity for identification as to how to improve the current level of skills. A tool with integration of constructive feedback is lacking. However, via identification of the stage of learning within steps of an individual procedure could provide this feedback. Via demonstration of steps that are showing a higher cognitive input, areas requiring further training are highlighted. Cognitive assessment may via this approach provide not only a useful assessment tool but may be used within training additionally.

The present paper [4] does highlight the current paucity and standardisation of assessment tools within robotics. Few tools have been developed specifically for addressing technical aspects of robotic surgery. The Global Evaluative Assessment of Robotic Skills (GEARS) offers one validated assessment method [5]. Additionally, several metrics recorded in the many robotic simulators available offer validated methods of assessment [6]. These two methods offer reliable methods of both assessing and training technical skills for robotic procedures.

It is now evident that validated methods for assessment exist; however, currently technical and non-technical skills assessments occur as separate entities. A true assessment of individual capability for robotic performance would be achieved via the integration of these assessment tools. Therefore, any assessment procedure should be conducted within a fully immersive environment and using both technical and non-technical assessment tools. Furthermore, standardisation of the assessment process is required before use for purposes of selection and certification.

Cognitive assessment requires further criteria for differentiation of skill levels. However, it does add an adjunct to the current technical and non-technical skill assessment tools. Integration and standardisation of several assessment methods is required to ensure a complete assessment process.

Oliver Brunckhorst and Kamran Ahmed

MRC Centre for Transplantation, King’s College London, King’s Health Partners, Department of Urology, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK

References

1 Yule S, Flin R, Paterson-Brown S, Maran N, Rowley D. Development of a rating system for surgeons’ non-technical skills. Med Educ 2006; 40: 1098–104

2 Undre S, Healey AN, Darzi A, Vincent CA. Observational assessment of surgical teamwork: a feasibility study. World J Surg 2006; 30: 1774–83

3 Flin R, Youngson G, Yule S. How do surgeons make intraoperative decisions? Qual Saf Health Care 2007; 16: 235–9

4 Guru KA, Esfahani ET, Raza SJ et al. Cognitive skills assessment during robot-assisted surgery: separating the wheat from the chaff. BJU Int 2015; 115: 166–74

5 Goh AC, Goldfarb DW, Sander JC, Miles BJ, Dunkin BJ. Global evaluative assessment of robotic skills: validation of a clinical assessmenttool to measure robotic surgical skills. J Urol 2012; 187: 247–52

6 Abboudi H, Khan MS, Aboumarzouk O et al. Current status of validation for robotic surgery simulators – a systematic review. BJU Int 2013; 111: 194–205