BAUS 2018 Highlights Day Two

BAUS Day 2. The Multidisciplinary Team Debate. Which way are you headed?

BAUS is certainly a UK-centric meeting. But we all share most of the same challenges in healthcare, and as an international urologist in attendance, the learning experience is often gaining insight into how different health systems tackle common problems with solutions and evolutions.

During day 2 prime time, the agenda tackled the current and future situation with MDTs in cancer treatment—multidisciplinary team meetings. For the USA, we might use the term Tumor Board. At MD Anderson we just say, “Urological Multidisciplinary Case Conference.” So yes, MDT is much more efficient.

The goals are straightforward in principle: 1) increase the quality and standardization of care, 2) improve access to expert imaging/pathology, 3) provide a “group” decision which may be more experienced than any 1 person. In the United States, each center is left on its own how to organize and conduct MDTs, although there may be requirements for inclusion as an NIH designated comprehensive cancer center. In the UK, it appears that MDTs are more of a compulsory element. Another key decision is what patients will be presented—all or selected. In the UK, it appears the goal has been to present everyone.

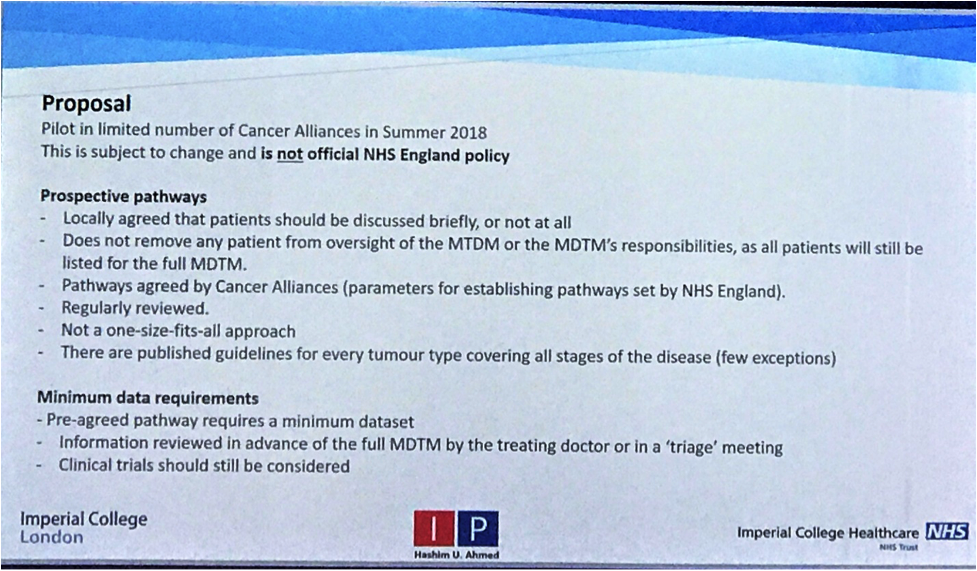

The first speaker was Hashim Ahmed who showed how the “present everything” model has increasingly become impossible, as half of all cases are presented/discussed in < 2 minutes and few go beyond 3 minutes. A national strategy is being discussed and likely piloted in prostate cancer whereby “routine” cases might be listed as a statistic but not discussed; and time reserved for more complicated cases where discussion might be more fruitful. This model will require the MDT chair to spend more pre-meeting time triaging the meeting agenda.

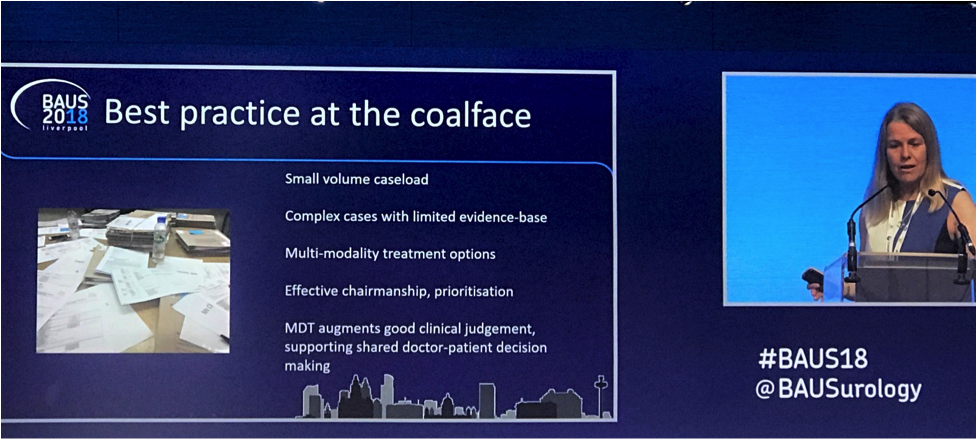

Jo Cresswell expanded the topic by compiling the UK real world experience with MDTs in terms of what has worked well and where it has been lacking.

The “good” might include:

- Building working relationships with colleagues

- Mentorship interactions

- Challenging old practices—evolving from eminence based to evidence based decisions

- Calling out bad practice/minimize rouge decision making

- Comforting patients that their case has been heard by a group—sort of a free 2nd opinion

The “bad” or “Pet Hates” list is interesting:

- The cost of running the MDTs—actual and effort

- Reduced ownership of the patient—notes where the plan just reads “refer to MDT”

- Waiting on the MDT

- MDT Tennis—i.e. referring back and forth between different MDTs

- Fatigue—going through 120 cases in a session—is anyone awake at the end? Some providers have to attend multiple MDTs per week

- Loud voices can overrule others (queue the photo of Trump)

- Agenda effect—if you always present in the same order then whoever goes last on the agenda probably gets less quality discussion.

What is the best middle ground? Again,the concept of discussion reserved for complex cases, and routine cases are under the MDT but not given time.

The final speaker was Bill Dunsmuir. He started by challenging the assumption that the MDT make up of 10-20 experts in oncology will produce wiser decisions than any single provider. Case and point was the 1996 climbing expedition to Mount Everest where the group decision making of expert climbers led to the deaths of the many. Maybe group thinking is not so wise? Problems might include group thought with the same ideas, hierarchy that minimizes dissent, and false debates.

From the Emperor of All Maladies book, he channeled the similar questions, “What is Cancer, why does cancer kill?” One trainee responded in a survey “A cancer killed because they were unfortunate enough to have their cases discussed at an MDT.” So why do we have MDTs?

His proposal was to consider MDTs as not only dedicated to group decisions, which may or may not always be right. Rather consider them as multidisciplinary professional education. As an example, if the group encounters a specific problem, there would be a pool of short video clips to review the evidence and guidelines—and then discussion could flow off of these standardized points. Ambitious for sure and would need funding and buy in.

In conclusion, this was a well-done session, and highlights the natural history, so to speak, of compulsory MDTs including all patients. At MD Anderson, we went the other way: select presentations. Each case takes 10-20 minutes, so we usually only get through 3-5 in an hour session. Attendance is optional and there tends to emerge faculty personalities who like MDT interaction, and some who never go. Cases are nominated by a fellow or faculty and you would probably be criticized for presenting a patient where we already have a treatment protocol in placed, i.e. “put them on the protocol, next case.” As a fellow in 2001-2002 I observed there are 3 popular categories of MDT case presentation that are always worthwhile:

- I dare you to operate on this patient (co-morbidity, prior surgery, obesity etc.)

- How to manage multiple cancers

- Look what they screwed up on the outside. Now what?

Please use our comment section—where do you stand on MDTs at your center and what is in the future?

John W. Davis, MD, FACS

Associated Editor, BJUI

Figures: Slide highlights on current and future of MDTs

The UK has certainly done a lot to advance the cause of multidisciplinary working. I was a trainee and consultant at Guy’s as the IOG and NHS Cancer Plan was getting rolled out, and it certainly cemented the role of MDT working, and also of the cancer nurse co-ordinator, in cancer workflows. All good.

However, the NHS obsession with targets and ticking boxes, also meant that compulsory discussion of all cases in MDT meetings became a rod to beat themselves with. Combined with centralisation of care and supra regional MDT meetings, these have become unwieldy. In Australia, MDT workings are not legislated as they are in the UK, but MDT meetings are now standard in all centres in the public system, and many centres in the private sector. The format is variable and depends on individual leadership. In our centre (a tertiary referral cancer centre), we devote plenty of time for complex cases, and don;’t discuss cases that we don’t think need to be discussed. Is that perfect? No. Does the meeting flow really well? Yes. A mixture of both systems is likely best.

Agree–clearly the panel of speakers did a good job reviewing a complex topic and showing a better pathway forward for the UK system.