Editorial: Tailored prostate cancer survivorship: one size does not fit all

One of the great triumphs in Urology is the transition of prostate cancer surgery from a universally morbid operation to one that now focuses on postoperative quality of life. This paradigm of cancer survivorship focuses on managing new, recurrent, or persistent symptoms. In this article by Bernat et al. [1], men within the Michigan Prostate Cancer Survivor Study were surveyed to identify factors that increase the need for additional prostate cancer survivorship information. Previous studies have shown discrepancies between subsets of prostate cancer survivors, based upon social, pathological, and treatment-based factors [2-5]. Indeed, the need for improved patient-centric information for all cancer survivors has resulted in the American Cancer Society publishing guidelines on how to best manage prostate cancer survivors, which account for four of every 10 male cancer survivors [6].

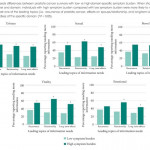

The authors [1] identify several critical aspects of post-treatment prostate cancer survivors. First, more than half of patients needed more information about their symptoms. This may be a departure from the views of many urological surgeons, who believe their patients are symptom-free after treatment. Second, the information needs of respondents were intuitively tied to their specific symptoms. For example, men who received combined therapy – thus, suggesting concern for incomplete control with primary treatment – were more concerned about recurrence; married men were more concerned about the effects of prostate cancer on their significant other; and men with more profound bowel or sexual symptom burdens were more concerned about the long-term effects and recovery period. Third, prostate cancer survivors remain concerned about diagnosis and treatment of their disease, even after they have received curative treatment. Topics such as early detection, diagnosis, and prevention of cancer were identified in double-digit percentages of respondents. Finally, there exists a correlation between the severity of symptom burden and associated information needs. A subset of symptoms (urinary, sexual, and bowel) may be directly related to treatment techniques and technologies. Thus, improvements in these fields may have long-term survivorship benefits.

While enlightening, these results are nevertheless susceptible to the inherent limitations of a survey-based study. Selection bias suggests that the true range of information needs and associated symptom burdens are not completely captured in these results. Additionally, these findings are not subdivided based on pathological stage or treatment method, which probably play important roles in cancer treatment, post-treatment symptoms, and patient concerns.

What are we to do with the results presented in this report? Clearly, easy access to informational resources about cancer survivorship needs to be offered as a standard of care for men with prostate cancer, which should be initiated before starting treatment. Additionally, men who are at-risk for requiring additional information on cancer survivorship (non-White race, received multimodality treatment, recurrent cancer, or high symptom burden) should receive additional counselling to ensure their informational needs are met. Finally, studies validating the effectiveness of these resources should be studied prospectively. Just as no two prostates are the same, so too should the paradigm be for prostate cancer treatment and survivorship.