Editorial: Routine data expose a need for change

Withington et al. [1], in their analysis of changes in stress urinary incontinence (SUI) surgery in England, have tapped in to a rich seam of information which, as well as holding the promise of much more, also highlights a need for changed thinking about services and training. They have produced an excellent review of the use of Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data to establish a pattern of changing surgical practice for the treatment of urinary incontinence in England. They rightly point out the great potential of using patient-specific linked data to explore other relationships between predictors and outcome. Widespread use of powerful data of this sort could, theoretically at least, help to answer research questions, as well as to plan service design and resource allocation.

The use of routine data by the NHS is a hot topic in the UK at present. An England wide database, Care.data, has been developed that plans to link anonymised routine data, automatically drawn from community care, hospital statistics, public health and social care databases. Whilst debate rages about the confidentiality issues, and conspiracy theories abound, some strident voices promote a vision of how such a databank will be used to address big health questions and to identify relationships between social conditions, healthcare and outcomes, which have not previously been possible. Similar projects exist in Wales and Scotland enjoying the acronyms of SAIL (Secure Anonymised Information Linkage) and SPIRE (The Scottish Primary Care Information Resource), and Northern Ireland also has plans in progress. These systems do differ subtly in detail but not in aspiration [2].

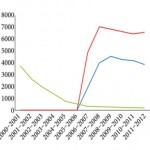

The authors’ findings confirm that lesser invasive procedures now dominate the treatment of SUI in women, and that the use of Botulinum toxin A for treating refractory urgency incontinence, despite the absence until recently of a license for its use, has become commonplace. Whilst demand for SUI surgery may have levelled off, following something of a surge in recent years, the demand for Botulinum toxin A treatment inevitably increases as patients become locked in to long-term retreatment programmes. With these numbers it should be possible for a hospital serving a population of, say, 250 000 to perform at least 40–50 of each procedure per annum. This is probably enough to sustain a routine service, consistent with recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), which described how surgeons should seek to maintain expertise through, amongst other things, having an adequate caseload [3].

Sacral neuromodulation (SNS), artificial sphincter, colposuspension, tape removal and augmentation cystoplasty are procedures that occupy the complex end of a range of surgical options for incontinence. These are patients who have often failed other treatments, defy easy categorisation, and are performed in relatively small numbers. SNS has not been adopted in the UK, as widely as might have been anticipated following NICE guidance in 2006, which strongly recommended its implementation – perhaps because of local difficulties in commissioning a procedure with such high capital costs. The low figures for all these procedures strengthen the argument to focus complex work into expert centres, where adequate numbers can be maintained and the next generation of specialists can be effectively trained.

Those who commission or plan service delivery, and those who design training programmes, need to take heed of this evidence. The nature of female and urodynamic urology has changed over recent years, now being characterised by 95% very routine procedures and 5% complex difficult cases. But if we centralise the 5% of complex work and leave those working in more peripheral hospitals able to offer only mid-urethral slings and Botulinum toxin A, then we have to reconsider the basis of specialist training. There is no point training a person to high levels of competence in complex procedures that they will never use in senior practice. The UK Continence Society is currently developing a set of minimum standards for service delivery and training, which will take this information into account.

The evidence presented by Withington et al. [1] is specific to England and it remains unclear how much these trends can be extrapolated to the UK nations with devolved healthcare, or indeed to other countries. However, Withington et al. [1] must be congratulated for highlighting both the power of routine data in clinical research, and specifically for identifying the dramatic changes in surgical practice of incontinence, which require an adaptive response from both the NHS and our specialist organisations.

Malcolm Lucas

Department of Urology, Morriston Hospital, Swansea, UK

References

- Withington J, Hirji S, Sahai A. The changing face of urinary continence surgery in England: a perspective from the hospital episode statistics database. BJU Int 2014; 114: 268–277

-

McCartney M. 2014 Care.Data; why Scotland and Wales are doing it differently. BMJ 2014; 348: g1702

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. September 2013. Urinary incontinence: the management of urinary incontinence in women. Clinical guidelines CG171. Available at: https://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed April 2014