Editorial: Optimal Thromboprophylaxis Remains a Challenge

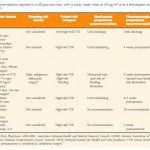

The ‘Guideline of guidelines: thromboprophylaxis for urological surgery’, published in this month’s issue of BJUI by Violette et al. [1], addresses a critical issue in urological practice and offers a comprehensive overview of available guidelines. Many urological surgeries, especially cancer surgeries, present a significant risk of thromboembolism, as well as bleeding. Therefore, urological surgeons should be well educated in the matter in order to be able to offer optimal prophylaxis to patients. Reading through the current recommendations and guidelines, one realises the wide variety of possible ways to risk stratify a patient, but also the large differences in opinions on how and when to offer prophylaxis. Consequently, even members within the same national society treat their patients in completely different ways.

The ideal recommendation will have to be individualised, taking thromboembolic and bleeding risk into account for each individual patient and specific surgery type. This stratification of patients not only presents a challenge in clinical practice but also for the design of meaningful clinical trials. As many medical questions regarding thromboprophylaxis remain unanswered, the currently available recommendations are based on our pathophysiological understanding and remain eminence-based, rather than evidence-based.

For many years, the ‘Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines’ [2] were viewed as the most respected guidelines in surgery. They include recommendations for a wide variety of surgical procedures, including urological surgeries. With an ageing population, our patients will more often be on anticoagulant treatment before surgery. While most guidelines still recommend stopping the anticoagulant treatment and bridging with heparin, new evidence from randomised controlled trials [3, 4] indicate that bridging by heparin significantly increases the risk for major bleeding without reducing the thromboembolic risk in most patients. Despite a recent appeal by internists and cardiologists [5], revised guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians to replace the partially outdated recommendations have yet to be published. As mentioned by Violette et al. [1] in their current review, bridging should probably only be offered to a limited number of patients with a very high risk of thromboembolic complications.

Whether the recommendations for acetylsalicylic acid prophylaxis will be changed similarly (to stopping perioperatively in all but high-risk patients) is less clear [6]. More clinical evidence is needed here.

The European Association of Urology has recognised the problem and presented the prospect of providing a guideline on thromboprophylaxis for urological procedures later this year. Looking at the landscape of available high-quality publications it will still be highly challenging to provide clear recommendations for urological surgeries. The key to a comprehensive application will be the clinical practicality. With this review, the authors have set the stage to a critical review of the recommendations from a urological point of view.