Editorial: PCPT May Exculpate COX Blockers in Erectile Dysfunction

NSAIDs are one of the most commonly used medications classes in the USA. Despite their ubiquity, they remain controversial. The withdrawal of the selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor Rofecoxib in 2004 was a low point, culminating in a >$4.85 billion dollar (American dollars) settlement by Merck Pharmaceuticals. More recently, in July 2015 the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) strengthened a ‘black box warning’ (warning that appears on the package insert) on all NSAIDs for increased risks of heart attack, stroke, and heart failure (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety). Given common vascular pathways in erectile dysfunction (ED) and heart disease, detrimental effects on sexual health have long been suspected as well. This month’s issue of BJUI provides a new perspective on this relationship and may help exculpate these common drugs [1].

It is thought that the cardiovascular risk of NSAIDs arises from inhibition of the COX-arachidonic acid synthesis pathway, which produces important mediators (e.g. eicosanoids like prostacyclin and various prostaglandin subtypes) for inflammation, vascular tone, and vascular permeability [2]. Given that many of the same chemical mediators affect erectile physiology, it is not surprising that a previous study of 80 966 men showed an association between NSAID use and ED after accounting for age, race, and comorbidities [3].

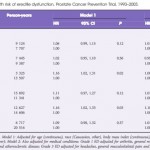

In ‘Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use not associated with erectile dysfunction risk …’, Patel et al. [1] show that this risk may not be what it once seemed. They assess the risk of developing ED for men in the placebo arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) after first reported NSAID use. There is a small but statistically significant and consistent relationship between initiation of NSAID use and ED. Curiously, the association of NSAIDs with ED disappeared once they controlled for the indications for NSAID use such as arthritis, chronic pain, headaches, and cardiovascular disease. This finding makes sense: common indications for NSAIDs, like arthritis, headaches, and chronic musculoskeletal pain, may indicate an underlying sedentary lifestyle or chronic inflammatory conditions, both imputed in ED [4]. As such, this study design provides key epidemiological inference on the causal links between inflammation, lifestyle, and ED. It may be these factors, not NSAIDs themselves, which account for the previously shown association with ED.

With that said, epidemiological assessment of eicosanoid-mediated effects on ED may require further study. For example, NSAID-mediated downregulation of endothelial signalling molecules could produce a short-lived, but clinically significant effect on cavernosal blood supply. Alternatively, ED may only arise in the setting of chronic downregulation of affected pathways. Epidemiological studies characterising the relationship between NSAID use and ED should therefore assess the amount and duration of NSAIDs use, as well as the quality and timing of erections relative to use. Basic research may also help elucidate this relationship. Earlier studies have assessed cavernosal endothelial concentrations of these same vascular mediators in diabetic animal models [5]. In a similar fashion in vivo assessment of COX-derived mediators using animal models could further characterise the vascular pathways involved in erection and the effects of NSAID use.

Patel et al. [1] add a valuable contribution to the study of NSAIDs and ED. Their finding that NSAID-induced effects on ED disappear when controlling for the indications of NSAID, may support the inflammatory hypothesis of ED. But as others have noted, there is an intrinsic difficulty in retrospectively assessing the complex, multifactorial causes of sexual dysfunction [6]. Future studies on the amount and timing of NSAID use, paired with biochemical studies of vascular mediators in the cavernosal endothelium in NSAID users, may allow for even more nuanced characterisation of the effects of COX inhibition on erectile function. While logistically challenging, such studies could provide the key evidence for assessing the vascular pathways underlying ED and their relationship with NSAIDs.