Editorial: Managing expectations after radical prostatectomy; time to change

There have been numerous advances in the management of prostate cancer. Developments in imaging, surgical and radiotherapy technology, and pathological grading, have led to improvements in the diagnosis and management of this common malignancy. Such progress has translated to earlier diagnosis and improved disease-specific outcomes.

With improved outcomes comes increased attention on life after treatment. Survivorship in cancer has been an area of increasing focus. The aim; to live as healthy and as good a quality of life for as long as possible after diagnosis, by managing the consequences of the cancer and its treatment. In prostate cancer, the functional impact of surgery on quality of life can be considerable, especially given the falling age at first presentation. The consequences of treatment are often the reason patients’ select one form of therapy over another.

Both sexual function and urinary continence can be significantly affected after radical prostatectomy (RP). Despite numerous consequences of surgery on sexual function, the greatest focus in publications is erectile dysfunction (ED). The quoted incidence in published studies can vary from 20% to 90%, depending on whether the return of ‘normal’ erectile function is classed as the return of spontaneous erections, a ‘return to baseline function’, or functional recovery only with pharmacological assistance. This lack of agreed definition of ED after RP hampers progress by underestimating the impact of surgery and making an uneven playing field when comparing studies.

The tendency for surgeons and studies to focus solely on erectile function, when there are so many changes in sexual function after RP, does not give patients a realistic expectation of the impact of surgery on their life after treatment. Patients should be made aware 100% will experience some change in their sexual function after surgery. Patients should be aware of all the possible risks, including;

- ED: All will develop a degree of ED after any RP and should be aware that their risk is dependent on their baseline function, comorbidity, and nerve-spare status. They should be made aware of the protracted time course for recovery, even when the nerves are spared, the need for possible injection therapy, and the possible future dependence on some form of therapy to achieve functional erections in the long-term.

- Changes in ejaculation: All patients should be made aware of the loss of ejaculation as a permanent feature, and the impact this will have on their natural fertility. They should also be aware that some develop climacturia, and the possible risk of ejaculatory pain.

- Changes to penile size/shape: Patients should be aware of the possible reduction in penile length after RP, and the increased risk of developing Peyronie’s disease after RP, which can further impact their sexual function.

With high profile advances such as the rise of robot-assisted RP (RARP), much has been made of the improved view of local anatomy, and ability to manoeuvre within the confined space. The expectation that this translates to improved functional outcome existed way before any studies had been conducted to show any benefit. It is of no surprise, therefore, that patients’ expectations of outcomes after RP have been unrealistically raised by such technologies.

In this month’s BJUI, Deveci et al. [1] present their survey looking at patient expectations of sexual function after RP. In this study, patients who had undergone RP (open or robot-assisted) in the last 3 months were asked to recall the counselling they had received about possible changes in sexual function preoperatively. The comprehensive approach of this study examined patients’ expectations in all the different facets of sexual function, including erectile function, expected time to full recovery of erections, the possible need for intracavernosal injections (ICI), changes in ejaculation including intensity, pain, and climacturia, and awareness of penile length changes and risk of postoperative Peyronie’s disease.

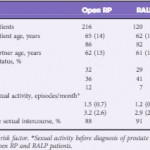

Compared with those undergoing open RP, patient’s expectations after RARP were greater, with more expecting a shorter recovery time (6 vs 12 months, P = 0.02), a higher expectation of a recovery back to baseline erectile function (75% vs 50%, P = 0.01), and lower expected need for ICI (4% vs 20%, P = 0.01) [1]. This greater expectation of newer technology leads to greater regret, and a greater need to manage expectations preoperatively [1, 2].

In addition to the misconceptions on erectile function, ~50% were unaware of the risk of anejaculation, <10% were aware of changes to penile length, and none were aware of risks of developing Peyronie’s disease after RP.

While the Deveci et al. [1] study does have flaws, primarily the lack of ability to differentiate between what patients were exactly told before RP by the nine different operating surgeons, and what could be recalled after RP, it does highlight an important point. No matter what patients were told before surgery, within 3 months of surgery their recollection and understanding of its possible impact on sexual function was poor. Previous studies have highlighted this disparity between clinician’s recall of discussions on the consequences of surgery and patient recall. In one study, while 100% of clinicians felt they had adequately addressed patients concerns on ED, <30% of patients felt the issues had been adequately addressed [3].

Effective management of patients’ expectations of the possible consequences of RP preoperatively allows for better informed consent, a realistic expectation of outcome and time course for recovery, better compliance with postoperative treatments for ED, and less regret of the initial surgical approach.

Given the limited time in consultations, there is not enough time to address all the possible consequences of surgery in detail. When being diagnosed with cancer, often the last thing on the patients mind is sexual function a year down the line. The more important issue at first is coming to terms with the cancer diagnosis, and just making it through the surgery. In addition, one has to wonder if it is fitting for the oncological surgeon to discuss the functional consequences, possible outcomes and their management when other specialists will manage this in the future. A discussion of sexual consequences of surgery is very different coming from the robotic surgeon, rather than the andrologist who would see them after.

The most ideal approach would be for all patients to see an andrologist and continence specialist before RP or be seen in preoperative ‘survivorship’ seminars, based on discussing possible consequences and optimising functional recovery after treatment. Such seminars should be run by the teams involved in managing sexual function and continence postoperatively. Patients should be given a simple, one page sheet outlining the possible consequences of their intended treatment, be that radiotherapy or surgery, on sexual function and continence. In the same way that patients are given a key contact for their cancer care, they should have access to a key contact for their functional recovery. In addition to follow-up visits with the operating surgeon, focusing on the oncological outcome, a separate follow-up based on functional outcome with an andrologist and continence specialist would focus on functional recovery.

There has been a drive to develop high-volume cancer centres of excellence, with pooled resources to allow excellence in imaging, pathology, as well as surgical and non-surgical treatments. The most utopian approach would see these centres also having andrology and continence specialists focused on the management of all postoperative functional consequences, including the ability to undertake penile implant and artificial sphincter surgery as required.

The progress in developing such an infrastructure has been slow. Research on optimising functional recovery has not been as extensive as the focus on diagnosis and treatment in prostate cancer, which can dominate many urology journals and meetings. This imbalance needs to be addressed, to provide not only the best treatment for prostate cancer, but also the best management of the consequences of treatment, aimed at improving quality of life after surgery.