Editorial: Fluorescence cystoscopy – the end of biopsies for CIS detection?

The present prospective study by Palou et al. [1], conducted in eight Spanish centres, documents the use of hexaminolevulinate fluorescence cystoscopy (FC)-guided bladder tumour resection and biopsies in 283 patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). It is an inpatient comparison between white-light cystoscopy and FC. The study presents data from routine practice in Spain and the results show an improvement in diagnosis of NMIBC, especially Ta tumours and carcinoma in situ (CIS) with FC-guided resections. These results are confirmation of reports in the literature, including a number of randomized controlled trials and a recent large meta analysis [2]. Although the magnitude of the difference between FC and white-light cystoscopy was somewhat lower in the present study, apparently even in normal daily practice the difference was significant. Moreover, as the rate of CIS in Spain is very high, up to 19% in a large Spanish series [3], I can imagine that the use of FC is of specific interest in this country.

Apart from the confirmation of the better detection rate (75.5 and 93.2% for white-light cystoscopy and FC, respectively, figures similar to those in the recent literature) and confirmation of safety of hexaminolevulinate FC, there are two particular points regarding the present study that I would like to highlight.

The first item that deserves some discussion is mucosal biopsies. In this study the number of false-positive results (948/1569; 60.4%) was very high. This was predominantly explained by the inclusion or mucosal biopsies from ‘normal appearing urothelium’ in these calculations. Only 36 lesions were detected with biopsies, which suggests a very low detection rate. Assuming that >800 random biopsies were taken (apparently six biopsies were taken per patient, and biopsies were taken in 49.1% of the 283 patients), the detection rate was <4%, and one might ask whether it was still worthwhile to take these biopsies. Even though 26.7% of patients with CIS were only diagnosed by biopsies in this study, the number was small. The authors also indicate that it was surprising that CIS was not found more often with FC, but they blame it on the learning curve for FC. The value of mucosal biopsies was also questioned by some reviewers, and in fact by the present authors too. In their introduction they explain the biopsy policy by the high rate of CIS in Spain; however, they also indicate that this incidence seems to be decreasing. Taking together the disappointing detection rate of mucosal biopsies and the high detection rate of CIS with FC, the message should be clear: stop taking mucosal biopsies from normal-looking urothelium. As a matter of fact, this had already been suggested before the era of FC by the authors of other large studies, such as an analysis by the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer [4] and a large Dutch study [5]. The false-positive rate for FC was not very high (15.7%, similar to the more recent studies with hexaminolevulinate FC). And I assume that these figures would even be much lower if biopsies of normal urothelium were to be excluded from these calculations.

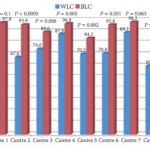

The second point that deserves attention is the learning curve for FC and its impact on the results. The authors indeed mention as an important limitation of this study ‘the investigators’ lack of experience’ with FC. They point out that this might be the reason that the advantage of FC for the detection of CIS seemed to be less pronounced than in published series, although still significantly better than with white light. In their cohort, 27 of 36 patients with CIS (75%) were detected with FC. The impact of the learning curve and the limited experience of some of the centres is also illustrated by the wide range between centres in, for example, the false-positive rates. Indeed, some training with this FC technique is mandatory. Unfortunately, however, the authors were not able to provide details of the relationship between experience and detection of CIS or false-positive rates.

In conclusion, even in routine practice, FC significantly improves the detection of NMIBC. The advantage is seen especially in Ta tumours and CIS, similarly to recent publications. The use of FC can, in my view, replace the use of random mucosal biopsies of normal-looking urothelium with white light because the detection rate of these biopsies is only a few percent. Finally, the present study also shows that a learning curve significantly improves the detection rate of NMIBC with FC and decreases the rate of false-positives. This should probably be somewhere between 5 (the number used in some of the registration studies for hexaminolevulinate) and 20 as suggested by a recent Canadian study [6].