Editorial: Does a positive margin always mandate adjuvant radiotherapy?

The appropriate treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer continues to generate controversy. For men with low grade disease it is unclear whether surgery or radiation therapy provides a survival advantage over active surveillance, and among men with high grade disease it is unclear how many derive a substantial benefit from either intervention. No trial has yet to compare surgery and radiation with observation, but the recent update of the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group 4 study suggests that radical prostatectomy provides a significant survival advantage for younger men with intermediate grade disease [1].

Unfortunately, many men undergoing radical prostatectomy are not cured of their disease. The Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group 4 study has shown that as many as 26% of men undergoing surgery developed distant metastases and 18% died from their disease after a median follow-up of 13 years. For this reason many clinicians recommend additional radiation therapy for those men undergoing surgery who are at high risk of disease recurrence. Three randomized trials now support the use of radiation therapy in this setting. Two have shown lower rates of biochemical progression and one has shown improved distant metastases-free survival and overall survival [2-4]. These trials compared the use of adjuvant radiation therapy with observation. Some clinicians, however, are reluctant to refer patients for radiation therapy because of concerns about its potential impact on quality of life. This is especially true for those patients who have yet to show any evidence of biochemical recurrence.

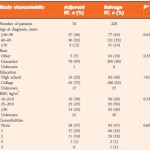

In a manuscript published in this month’s BJUI, Hsu et al. [5] have turned to a large national prostate cancer registry that has accrued men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer since 1995. They evaluated the long-term outcomes of these men to gain insights into whether a delay in the initiation of radiation therapy compromises survival. Their findings suggest that delaying the initiation of radiation therapy until there is evidence of biochemical recurrence does not seriously compromise long-term outcomes and avoids radiation in some men who are never destined to have disease progression.

The authors are appropriately cautious with their conclusions and clearly recognize the limitations of a non-randomized study. In a registry study it is impossible to control adequately for selection biases. Men receiving adjuvant therapy had no evidence of biochemical recurrence at the time radiation was started. This group of men included both men who were destined to have disease progression and men who were destined to maintain an undetectable PSA. This differs from the men receiving salvage radiation therapy. All men receiving salvage radiation had evidence of disease progression and therefore their tumour burden and their long-term prognosis was probably worse when compared with men receiving adjuvant therapy. Despite this selection bias, men initiating salvage radiation when their postoperative PSA level was still <1.0 ng/mL had similar long-term outcomes when compared with the men receiving adjuvant radiation. Men with postoperative PSA levels >1.0 ng/mL had a much higher risk of aggressive disease and a worse outcome.

Ideally, the question about the timing of postoperative radiation would be subjected to a randomized trial. Until then, the information provided by Hsu et al. provides strong clinical support for a practical approach to the question of who should receive postoperative radiation. Men who are clearly at high risk of disease progression, which includes men with Gleason 8–10 disease and those with extensive margin positive disease and seminal vesicle invasion, should probably receive adjuvant radiation therapy as soon as they have recovered from surgery. For men with Gleason 7 disease or those men who have focal margin-positive disease it may make sense to monitor postoperative PSA levels closely and refer men for postoperative radiation when there is evidence of biochemical progression and before the PSA level reaches 1.0 ng/mL. This approach would spare some men the need for additional treatment and would defer treatment for many years in others. Men who are eventually found to have biochemical recurrence should feel reasonably comfortable that the delay in initiating radiation therapy is unlikely to have caused any significant compromise of their long-term outcome and probably improved their quality of life.

Large case series analyses frequently have selection biases that confound conclusions. In this instance the authors have cautiously interpreted a large community-based registry to gain a valuable insight into the management of localized prostate cancer. Their analysis provides appropriate support for their conclusions.