Clinicians and their cameras

15 years ago, many people reading this blog won’t have even had a mobile phone! Fast forward to today and we wouldn’t leave home without it. Not content with just having a phone, we now crave the multimedia functionality of smartphones which dominate the market. With this ability to spread and share information so easily comes medico-legal dangers, not only for individuals but also hospitals concerned about patient confidentiality for which they are corporately responsible.

Not long ago, taking a picture of a medical condition for any purpose was a major effort. Contacting the medical photography department of the hospital would take an age and often the moment would be lost. Things began to change with affordable digital cameras although images were usually stored in one location on that camera, often locked away. This situation has altered completely with mobile phone now offering cameras capable of extremely high quality photography (I don’t own one but the Samsung Galaxy S4 possesses a 16MP lens offering far greater resolution than my digital SLR which is only a few years old and Nokia have just released a 41MP cameraphone!). Here you will get the brief idea about the wired vs wireless security system. Suddenly if we see an interesting condition, we can whip our phones out, take a picture and immediately send it round the world on social media platforms. Even if the photos are just stored on the phone, with these being such desirable objects for thieves, this poses a significant risk to loss of that data and potential breach of patient confidentiality. It used to be that CCTV cameras were all that was required to ensure that things ran well in terms of security within a business. Tough circumstances, on the other hand, necessitate even harder measures, which necessitate the installation of detection and alarm systems. The fact that these commercial access control systems are available in a number of models is the nicest part about them.

So where am I going with this ? Well, I read with interest a recent article on “Clinicians and their Cameras” in Australian Health Review 2013. In this survey of one hospital in Australia, one fifth of clinicians reported using their personal mobile phones for medical photography. The authors describe as “endemic” the non-compliance with policy requirements for written consent for these images. Only 6% disposed of the images according to hospital protocol. What is scary is that I suspect the use of personal mobile phones may be under-reported!

There are many benefits to being able to immediately take a medical image in an appropriately consented patient. It may allow a condition to be tracked e.g. serial photographs of cellulitis; or allow discussion with a senior doctor where the most salient image e.g. the infected wound or an x-ray could even be sent to the consultant at home to review. These moments require spontaneity or the chance is lost.

Many hospitals, certainly in the NHS in the UK, completely ban the use of mobile phones for photography. This is an understandable corporate response to the problem which includes consent, confidentiality, appropriate use, storage and disposal.

Medical staff clearly need to be aware of the ethical issues and regulations regarding the use of medical images. The European Commission has found that collection of medical data and maintenance of medical records fall within the sphere of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Thus failure to comply with regulations not only contravenes policy from your employer and regulatory body but also breaches the patients human rights. In the UK the Data Protection Act states that all organisations have a legal obligation to protect personal data which would include an individual taking images on any device and thus non-compliance also breaks the law.

The General Medical Council (GMC) in the UK has guidance on visual and audio recordings of patients. This makes clear the following points:

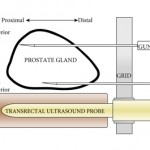

- Appropriate consent must be obtained. This seems obvious although the guidance does say that separate consent is not necessary for images of internal organs, images of pathology slides, endoscopic images, x-ray and ultrasound images. These maybe used for “secondary purposes” without seeking consent if appropriately anonymised and non-recognisable. However this only applies if they are taken as part of the patient’s care. Images for research, teaching or training require appropriate consent which should be stored with the image.

- All images should be anonymised/coded for storage. What mechanisms exist for this in your hospitals?

- Images should be stored securely and follow local procedures and protocols. Fine in principal but how does this work in practice?

- Recordings or images form part of the medical record. So if we do take an image we are responsible for ensuring it is accessible as part of the medical record.

But what about the unexpected finding in the middle of a case? The GMC guidance is clear: In this situation “you must not make recordings for secondary purposes without consent”. So you need it in advance if you are going to do it.

This study suggests that the use of mobile phones for photography in hospitals is commonplace and local protocols are not met. This is likely to be a widespread problem in hospitals in many countries. In my hospital the policy is clear: NO PHOTOGRPAHY ON PHONES OR PERSONAL DEVICES IN THE HOSPITAL. Any breach of this is a disciplinary offence. This prompted the following response from one of my colleagues: “This is ridiculous on many fronts. Bad for patient care, bad for education”. From a managerial perspective I can understand this. From a clinician’s point-of-view, I find this very sad with multiple opportunities lost for improving patient care and medical education. In a highly regulated workplace these rules are likely here to stay and we must all ensure we are compliant with them to avoid potential disciplinary action. I would be interested in the experiences and opinions of readers from other hospitals and countries.

Matthew Bultitude

BJUI Associate Editor

This is as controversial as live surgery and its educational value. In many ways even more topical and relevant. Ignore official guidance at your peril.

An easy mistake is forgetting cloud sharing settings on smartphones that default to sharing medical photos on multiple devices with variable security. Hard to resist “missing the moment” as you say Matt

If the picture is anonymous, why can’t we take/use them for clinical purposes? It is an example of too much bureaucracy making life difficult for physicians. The technology is there, why not adapt the rules with these new technologies rather than stifle the use of the technology? Is anyone going to be physically harmed by taking an anonymous intra-operative photo? No. Could that patient (or another) benefit from it? Yes. There is no issue about photographing gross pathological specimens post removal from the body, why is there such a difficulty in whether you can take a similar picture with the organ in situ in the body? Times change, and rules and guidelines need to adapt also.

Matt

Great blog and very topical and contentious area. I wasn’t the person you spoke to in the dept but I do agree.

I sympathise with David that “why cant we just take anonymous pics?”

Well because it is against the rules.I think the rules will catch up, and certainly need to,but at present BEWARE

Most doctors I know have pt pics on their phones and this is almost certainly against the protocol in their trust.

The irony is that most photos one could take would be to help the patient or educate other doctors so one might feel morally justified almost all the time. eg Pictures of an excised or histological specimen to show the patient, pictures of a scan to ask for an second opinion, pictures of a wound received from an on call spr to assess need for debridement.

all useful examples of using this technology to improve pt care- but currently all outlawed.

If this was ever enforced and phones inspected.. well that would be difficult for many.

lets all just be much more careful with this issue until things change.

Nice blog Matt. Shame its not a referenced Pubmed article as this is an important topic and no doubt your ‘paper’ would be cited many times due to the lack of information in this area.

In the States, the rules as far as I can see are the same. No photos without consent. Doesn’t matter how you take the photo.

In my current hospital (VA Ann Arbor) there are explicit warnings to the entrance of each operating room reminding the surgeon that mobile device photo capture is forbidden!

But mobile photos are an important clinical tool as Ben alluded to. They have helped me in the last few years: patient with suspected post-op wound infection sent us a picture of the wound versus traveling 100 miles, and you know what – it looked OK and we managed it conservatively. He didnt need to come in. Now is that not advancing the patient journey and care?

And of course, how many of us have asked to see the real severity of the curvature of the penis secondary to Peyronie’s disease from a patient’s smartphone?

Just like social media, with the changing tides, we need some guidelines in this area from our professional bodies – BAUS/AUA/EAU are you listening?

Rather than working as a team together for the benefit of patients. It is a very sad day that we are now thinking of smart phones and IT.

It is a very important current topic, our trust have set guidelines on medical photography – and should it not be included on the consent form? especially if the trust is part of a teaching hospital.

recently we had an incident of unconsented incident, we all have to be careful as icloud can be hacked.

Don’t confuse high pixel counts with higher resolution. A 41MP Nokia camerphone does not have twice the resolution of a 20MP D-SLR; the SLR out-performs the cameraphone by a long way. Sensor size is just as important. D-SLRs have large sensors (the larger the better) whilst cameraphone sensors are necessarily very small (to fit into a small package). For the best resolution in clinical images a D-SLR always gives the best results, but cameraphones are, of course, pretty “cool”. If you try enlarging your images to something like 30cm square, you’ll soon see the difference!

Clinical photographs are vital for educational work as people have said. I am particularly concerned about pictures of feet which are anonymised causing problems. There is no opportunity like an instant picture to show pathology and size. Lectures, publications and clinical value are all important to me and it is a shame that access is being made more difficult due to blanket rules. I have never found a patient refuse a foot photo but I have found some incandescent nurses causing a stink when that bit of pathology would be lost forever. I still have photos back to 1981 and would be reluctant to lose these.