Abandoning PSA screening: What is an acceptable price to pay?

The PSA screening debate continues to rage with conflicting advice from various bodies as to appropriate guidelines for men considering prostate cancer screening. In Australia the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand (USANZ) has supported offering screening to men aged 55-69 [Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand Position Statement on PSA testing 2009], as has the Royal Australasian College of Pathologists [Royal College of Pathologists Australia Position Statement on PSA testing 2014], however the guidelines for General Practitioners is yet to endorse this approach. A consensus group gathered by the Cancer Council of Australia, including Urologists, Oncologists, Epidemiologists and consumer advocates have recently put together proposals being considered by the NHMRC that recommend screening in men of an appropriate age with >7 year life expectancy, as long as active surveillance is offered to those diagnosed with low risk disease [Cancer Council Australia: Draft Clinical Practice Guideline PSA Testing and Early Management of Test-Detected Prostate Cancer]. The US Preventative Service Task Force Grade D recommendation against screening has been well documented, yet widely criticized for failing to include Urologists in its deliberations – the very specialists tasked with evaluating and treating localized prostate cancer.

Screening trials have reported conflicting results [Schroder et al, Pinsky et al], however with longer follow-up it becomes easier to demonstrate a survival advantage in men who are screened, and this does not even directly take into account the reduction in morbidity from advanced disease in populations as a result of early detection.

The issue at hand seems inherently very simple – that mass PSA screening will inevitably lead to overdiagnosis and, if a conservative approach is not adopted in low-risk disease or men with significant co-morbidities, overtreatment. Since PSA testing was introduced, the natural history of prostate cancer has become better understood [Albertsen], along with the understanding that many men with prostate cancer harbor “clinically insignificant” disease. Urologists have recognized this internationally and developed active surveillance protocols in response [Kates et al, Klotz]. Here in Australia the Victorian prostate cancer registry now confirms a significant number of men with low-risk disease being managed conservatively [Evans].

In the meantime, however, the pendulum is swinging the other way, and on the back of the USPSTF recommendations we are now seeing evidence of a drop in PSA screening. Confusing the debate is the extrapolation of negative studies to men of an entirely different population (e.g. using the Prostate Cancer Intervention vs Observation Trial [PIVOT], which comprised an average age of 67 to conclude that men in their 50s will not benefit from screening), poor design of the reported screening trials (e.g. the PLCO trial, which formed the backbone of USPSTF recommendations but due to compliance/contamination compared a population of 52% screened vs 85% screened), and the accusations of vested interests, particularly when Urologists take a pro-screening position (just read comment section on BJUI 2013 report of “Melbourne consensus statement on prostate cancer testing”)

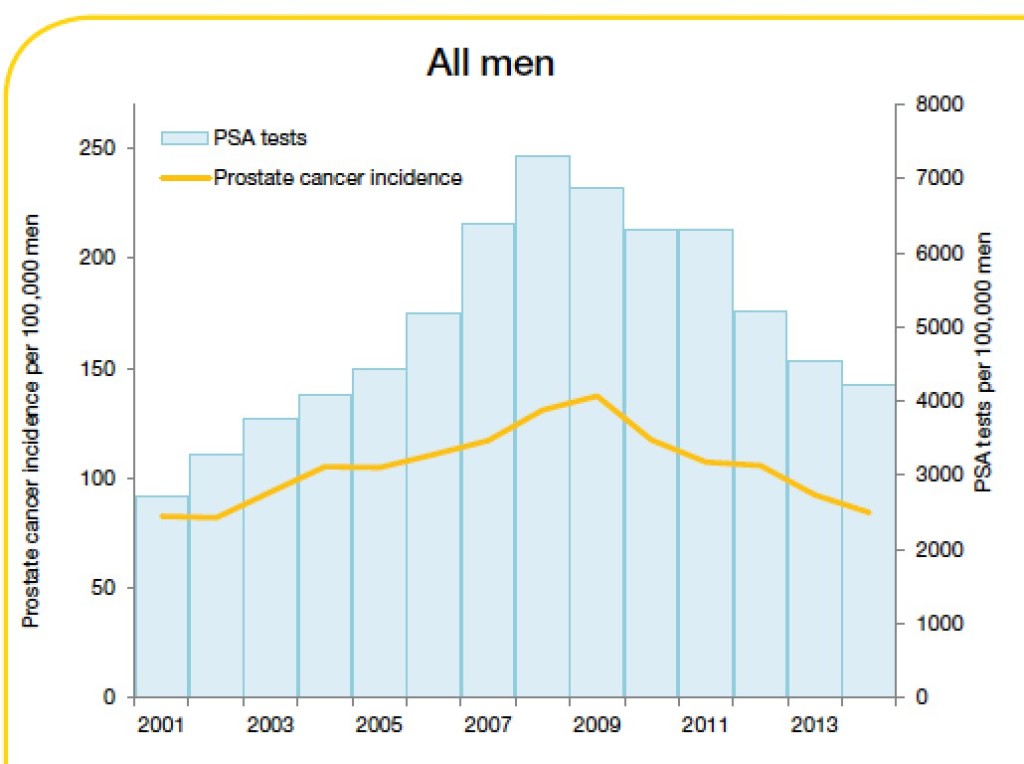

What is the end result at a population level? In Victoria, Cancer Council data confirm a drop in prostate cancer screening and diagnosis [FIGURE]. There is no reason to believe that true prostate cancer incidence has suddenly declined, and we can conclude therefore that the negative publicity surrounding PSA screening is having an impact and less men are undertaking screening and diagnosis; a reversal of the jump in incidence that occurred when PSA testing was first introduced. Is this a bad thing though? Could this just be that we are finally reducing the diagnosis of clinically irrelevant cancers that are the bane of a PSA screening programme?

Trends in prostate cancer incidence and PSA testing rates, 2001-2014

Source: Cancer in Victoria: Statistics and Trends 2014. Cancer Council Victoria

My disclosure is that as a Urologist with a subspecialty practice in prostate cancer management, I deal at a personal level with patients, rather than population statistics, and in the last few months alone, multiple patients have highlighted for me the sacrifice we must admit to making if we are to abandon or even discourage PSA testing. A few specific cases are worth sharing as scenarios that GPs could consider including in the risk/benefit discussion required before ordering a PSA test.

Case 1:

64-year-old, well man with no relevant past/family history was referred with a rising PSA from 3.9μg/L in 2010 to 6.6μg/L in 2011. No abnormality was found on rectal examination and a biopsy was advised but refused given contemporary publicity in the lay press outlining the risk of biopsy and harms of overdiagnosis/overtreatment. Over the next 5 years the patient undertook various natural remedies and in 2014 when the PSA was 13.3μg/L, an MRI was performed that demonstrated a PIRADS 4 lesion. It was only until 2015 when the PSA had reached 21.9μg/L that a biopsy demonstrated a significant volume of Gleason 9 adenocarcinoma, with pelvic lymphadenopathy on staging.

Case 2:

A 57-year-old man requested PSA screening in 2013; however, he was advised by his local doctor that this was unnecessary based on current guidelines. In 2015 the patient’s brother was diagnosed elsewhere with prostate cancer and underwent radical prostatectomy. The patient then demanded a PSA, which was performed and found to be 40μg/L. Rectal examination revealed a firm, clinical stage T3 malignancy and biopsy demonstrated extensive Gleason 4+4 prostate cancer.

Case 3:

A 51-year-old man was found in 2010 to have a mildly elevated screening PSA of 4.5μg/L. Despite repeated recalls from the GP to have this repeated and further investigated the patient refused until in 2015 he presented with obstructive voiding symptoms and was found on examination to have a diffusely firm, clinical stage T3 malignant prostate. Repeat PSA was 39μg/L and subsequent investigation confirmed extensive Gleason 9 prostate cancer with positive pelvic lymph nodes.

For these men curative treatment is probably no longer an option. Whilst a small anecdotal group, these are real men seen at a community level who demonstrate the power of PSA screening to identify aggressive, clinically significant disease, at an early, curable stage. This is the coalface that General Practitioners and Urologists work at. When the USPSTF ratifies the Grade D recommendations on the basis of flawed and often misinterpreted trials in the absence of specialists who treat such patients, when Epidemiologists and well-meaning Oncologists who never see or evaluate localized prostate cancer lobby against the harms of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, they are condemning these men, and many others, to suffer and die from a preventable disease.

This risk of increased advanced cancer in a non-screened population has already been foreseen and reported [Scosyrev]. How many such men is it acceptable to sacrifice in the name of preventing overdiagnosis and overtreatment?

Rather than the knee-jerk response to abandon PSA testing, the answer, which is increasingly accepted by Urologists, is clearly to unlink prostate cancer diagnosis from treatment. It is to improve diagnostics as we are seeing with development of multiparametric MRI and molecular/genetic markers to make screening and treatment selection smarter. I fear that if this is not more widely accepted and the current situation continues, it is helpful that so much research is being conducted in the management of men with high-risk, oligometastatic and advanced disease, because it will be more and more of these cancers that we will be treating.

Dr Daniel Moon is Director of Robotic Surgery at the Epworth Healthcare, and a Urologist at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Melbourne

@drdanielmoon