By Tim Dudderidge

The da Vinci surgical system delivers the benefits of laparoscopic surgery with an easier and more precise human–tissue interface than conventional laparoscopic instruments. Nearly all major uro-oncological procedures are being performed robotically. In this issue of BJUI, Cheney et al. [1] present their technique and initial experience of robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RA-RPLND) for patients with primary and post-chemotherapy non-seminoma germ cell tumours. Quality indicators for RA-RPLND include adequate clearance of the desired surgical field, satisfactory lymph node yield, acceptable perioperative morbidity and length of stay, as well as longer-term functional and oncological outcomes. So how well does RA-RPLND stand up to scrutiny?

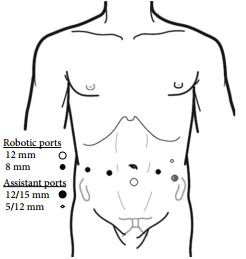

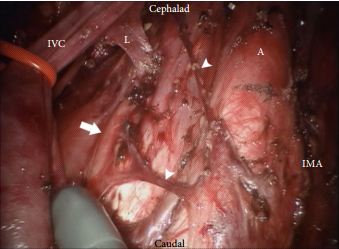

The technique employed by Cheney et al., placing the robot at the head of the patient, is unfamiliar to most urologists I suspect. It appears to offer excellent access to the retroperitoneum, but still requires a re-docking when performing full bilateral dissections. Whether this technique is superior to the lateral approach that I and others have used for modified dissections requires further study [2,3]. The lymph node yield was lower than that previously reported for open RPLND and while Cheney et al. [1] observe this may be due to the use of a modified template where appropriate, the absence of any in-field recurrences at a median of 22 months is perhaps the more reliable sign that there is oncological equivalence. Concerns that a true template dissection cannot be completed with a robot-assisted laparoscopic approach are probably unjustified in my opinion. The description of surgical technique by Cheney et al., including suture ligation and division of lumbar vessels, confirms that if a surgeon is minded to do so, a complete bilateral or modified template clearance can be completed.

The absence of significant complications in this series is impressive; however, there were three out of 18 conversions to open surgery. The mean length of stay of 2.4 days is close to the 3–4 days stay I would expect after an uncomplicated open RPLND in a young fit man. However, 1–2 night stays were seen in their later cases as they gained experience. Perhaps more importantly in a group of working age men, return to full physical activity within 3 weeks is possible [2].

As highlighted by Cheney et al. [1], minimally invasive primary RPLND has been previously reported both by laparoscopic and robotic approaches. Their larger series provides an important demonstration that the robotic approach facilitates the more complex undertaking of post-chemotherapy RPLND. Furthermore they show that except for operative time, all other outcomes were similar in primary and post-chemotherapy cases.

As an enthusiast for minimally invasive therapies, I of course welcome these results and think that along with other published and presented series, they provide sufficient evidence to consider a more formal evaluation of this approach. However, how feasible is the wider introduction of RA-RPLND? Despite having experience of robotics and working in a team performing around 30 RPLNDs a year, I was only able to identify five cases during a 1-year period suitable for a robotic approach. With experience this could have been a higher proportion, but it is fair to conclude that suitable cases in typical cancer centres would be limited in number. This is particularly so for the UK and other European countries, where primary RPLND is not used. Cheney et al. [1] had similarly low numbers each year and recruited their cohort of 18 cases over 5 years.

An international multicentre registry is arguably the best way to gather more information on the safety and completeness of template dissection RPLND. Existing registries, e.g. the BAUS complex operations database, have already provided valuable insights into the results of RPLND in the UK [4] and could be combined with other international RA-RPLND databases already being compiled (Erik Castle MD personal communication). Partnership of testicular cancer surgeons without robotic experience with experienced robotic surgeons may also facilitate the development of additional centres for development of this procedure. They will also aid optimal patient selection and help avoid incomplete template dissections, which may compromise the excellent cancer control we are now used to.

There are clear potential advantages with a minimally invasive approach to RPLND, not least of which are the avoidance of a laparotomy scar, the reduction of complications and an earlier return to normal activity. Cheney et al. [1] have shown that their technique is feasible, safe and effective in the medium term and their results justify wider consideration of the procedure for further study and improvement.

Tim Dudderidge

University Hospital Southampton, Southampton, UK

References

1 Cheney SM, Andrews PE, Leibovich BC, Castle EP. Robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection: technique and initial case series of 18 patients. BJU Int 2015; 115: 114–20

2 Dudderidge T, Pandian S, Nott D. Technique and outcomes for robotic assisted post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) in Stage 2 non-seminomatous germ cell tumour (NSGCT). BJU Int 2012; 110: 97

3 Dogra PN, Singh P, Saini AK, Regmi KS, Singh BG, Nayak B. Robot assisted laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in testicular tumor. Urol Ann 2013; 5: 223–6

4 Hayes M, O’Brien T, Fowler S, BAUS RPLND Group. Contemporary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) for testis cancer in the UK – a national study. J Urol 2014; 191 (Suppl.): e89–90